Andrew Walker

Further Sources in the Historical Record

The previous post focused on traces of Gypsy history in census reports. This post focuses on what kinds of evidence of Gypsies’ lives can be gleaned from the pages of local newspapers in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, though the reporting has to be treated with significant caution. As before, Gypsy voices themselves are almost entirely absent; others always assumed the right to speak for them, thus frequently perpetuating stereotypes rather than understanding. Also discussed are the emergence of cultural tropes associated with imagined ‘pure’ Gypsy life, and some of the unexpected places in which to find Gypsy history.

Gypsies and Courts in the Local Press

Much of the coverage of Gypsies was connected with their court appearances and was generally hostile. The law, then as now, was largely designed to deter Gypsies from pursuing their ways of life. For instance, swingeing fines were applied to Gypsies for camping on common land, in order to deter repeated visits. At Kirton, near Boston, it was reported in 1840 that Thomas Smith had pitched a tent near the highway, contrary to the provisions of the Highway Act and, since the parishioners had long been annoyed about Gypsies camping there, were keen to use this

legislation to prevent them pitching tents, making fires or encamping on their highways. Smith was convicted and fined 1s. and 17s. costs.[1] Six Gypsies were fined £87.9s. for unlawfully camping with seven vans on the highway in the hamlet of Kelstern near Louth in 1874: even the Lincoln Gazette was moved to comment that this was ‘a pretty expense for one night’s camp’.[2]

In some cases, it was not entirely clear why Gypsies were being punished. In 1846, for example, the Lincolnshire Chronicle reported tersely with no further details, that at the Sessions House in Boston, two Gypsies, John Horring and Newcomb Boswell, were convicted ‘as rogues and vagabonds and committed to prison to hard labour for a month.’[3]

It is possible from such court reports to gain additional information about Gypsy communities. For example, encampments generally seemed to consist of 50 or fewer people, with no more than seven vans and 20 horses.[4] In many reports of legal cases, witnesses refer to groups not exceeding two or three Gypsy caravans in convoy.[5]

Reinforcing the discriminatory language employed in newspaper reports of Gypsies’ activities in the county, the tone regularly adopted can be gauged from some of the following examples of the reporting style used, which had much in common with racist tropes describing other minority groups. In one report, Gypsies were defined as ‘a nomadic and dangerous people’;[6] in another, they were described as ‘smoking their black pipes and using language not fit for ears polite’.[7] Elsewhere, Gypsies were accused of talking ‘so fast and in such a confused and ignorant manner that it was difficult to make out…’[8] The Louth Standard noted of a group of Gypsy men outside court, that magistrates ‘would have known how difficult and impossible it was to identify one from another …’[9] In 1889, following an outbreak of typhoid near Heckington allegedly associated with a recent visit of Gypsies, the Lincolnshire Free Press declared that ‘These nomads have very little regard for the public’ and they ‘disseminate disease and devastate families.’[10] In dealing with the outcome of a mass Gypsy fight at Haxey on the Isle of Axholme in which Riley Smith was seriously assaulted, Mr Justice Cave observed at the Lincoln Assizes in November 1883 that this was ‘an extraordinary case and certainly showed what very strange people there were living up and down in out of the way parts of Lincolnshire.’[11]

On occasion, when Gypsy families chose a more sedentary lifestyle, newspapers reported on such developments very positively. In 1857, the Stamford Mercury included a report of a group of Gypsy families deciding to settle down in homes in Nettleham, where men and women took up agricultural work locally. This article was reprinted in numerous papers across the country, including the Illustrated London News. As the report declared: ‘At last, even gipsies are melting into civilisation, the green and gorse-covered roadside spots where they used to camp in security being enclosed… At first the villagers did not take to their new neighbours very willingly but by degrees distaste died away.’[12]

Romantic and Exotic Representations of Gypsies

Whilst in most news reports, especially accounts of court proceedings, Gypsies were represented extremely negatively, the same newspapers carried stories that cast them in a very different light. Stuart Baker wrote a lengthy piece, ‘Lincolnshire Reminiscence’, for the Grantham Journal in 1922. It was based on a meeting between Baker and a long-term acquaintance, ‘Jasper, a Romany’. The Gypsies’ distinctive culture was described almost nostalgically, with references to Jasper’s ‘rickety caravan’ and ‘round-roofed tent’. The Gypsies’ fondness for the pied wagtail, their lucky bird, was also mentioned. A liberal sprinkling of Romany terms adorned the article – including ‘chals’ (children), ‘gorgio’ (non-Gypsy), ‘lavengro’ (collector of Gypsy words), and, perhaps inevitably, ‘hotchi witchu’ (hedgehog). The article went to describe in detail how Gypsies cooked hedgehogs, baking them in clay, which, when broken, brought with it the prickles and the skin. As Baker observed, ‘The flesh is beautifully white, fine and tender and resembles that of chicken.’[13]

Another country-based columnist, this time in the Sleaford Gazette, made much of the Gypsies’ use of hedgehogs. In an article entitled ‘November weather’, Rev. A.R. Tucker recounted his meeting with a Gypsy who told him that hedgehog oil – obtained after lightly baking the creature and straining the resulting liquids into a jar – was good for deafness and for applying to the head, which was ‘the reason why gipsies have such wonderful hair’.[14]

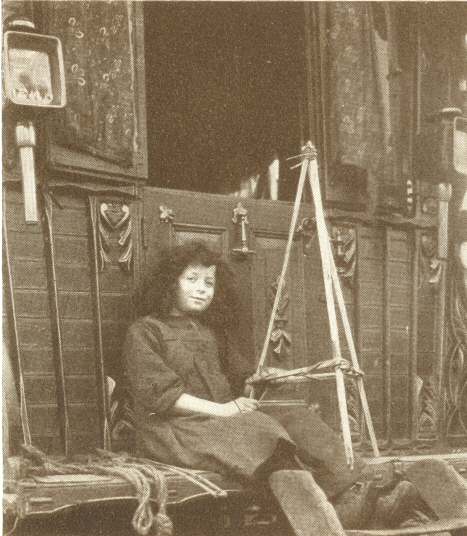

This type of somewhat nostalgic reporting, seeking to highlight supposedly ‘pure’ Gypsy culture and language, echoes early articles published in the journal of the Gypsy Lore Society and the mid-nineteenth-century work of George Borrow. His close affinity with Gypsy people prompted his writing of works such as Lavengro, published in 1851, and Romany Rye, which first appeared in 1857.[15] By the 1870s, there seemed to be a belief that Gypsies in England were ‘fast dying out’, the result of mixed marriages and other social and economic factors, such as the rise of high (improved and intensive) farming and the increasing value of the land which ‘interfered with them sorely’. The increasing presence of the rural police, it was suggested, ‘is likely to sweep them out of the country’.[16] It was against this background of a perceived endangering of the culture of the ‘pure’ Gypsy that the Gypsy Lore Society was established to record and celebrate Gypsy culture.[17]

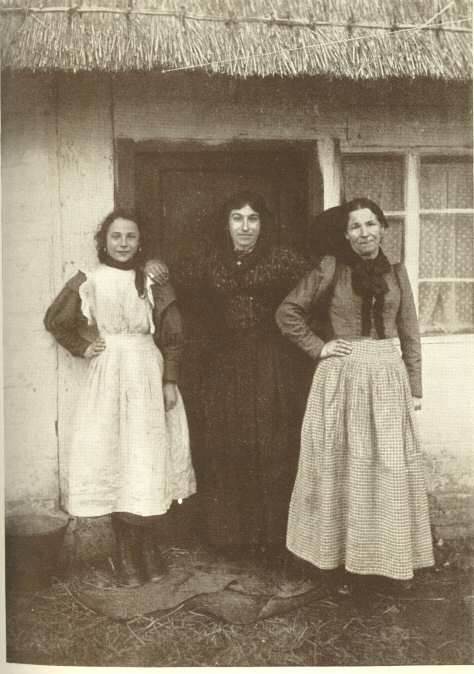

In this perspective, Gypsies were evoked as romantic, ‘pure’, even exotic, but certainly unthreatening, in marked contrast to the court reports. The ‘pure Gypsy’ was a recurring cultural motif through the second half of the nineteenth century, and was evidently extant in Lincolnshire. In addition to the examples cited above, its appeal seemed especially prevalent amongst women. Gypsy-inspired clothing appeared to be in demand at certain times. The Grantham Journal noted in August 1855 that the ‘new gipsy hat is so fashionable among the ladies’.[18] In the 1890s, no fund-raising bazaar was complete without a stall or a tent in which middle-class women could dress as Romantic-inspired, often mainland European, Gypsies. In the Gypsy tent at a grand bazaar at Woodhall Spa in 1893, six ‘ladies officiated, attired in the picturesque dress of the Spanish gipsy’.[19] In aid of Grantham’s St Peter Hill Congregational Church, an ‘Eiffel Tower’ Bazaar was held, with a model of the newly-constructed Parisian building at its centre, and a band played, with a ‘gipsy chorus’, alongside the staging of a ‘gipsy wedding beneath the greenwood tree’.[20]

Real Gypsy weddings were reported in the Lincolnshire press fairly regularly, though often the marriages occurred beyond the county borders. In one account, a Gypsy wedding at Billingborough was described as a ‘spirited affair’, which ‘passed off with eclat.’[21] In another more detailed report of 1864, the Louth and North Lincolnshire Advertiser described the coming together of two Gypsy families, the Browns and Grays, at Ulceby, which it described as ‘the metropolis of the two tribes, which are offshoots of the Boswell tribe’. The bride wore a muslin dress, a loose light-coloured robe and a pair of farmyard half boots; the groom wore corduroy fustian. One of the party was dressed in an infantry coat of brilliant scarlet with white facings.[22]

The size of some of these events was made clear in an account in the Stamford Mercury of a wedding of a 21- and 22-year-old at Fletton Church, just outside Peterborough, near the recent Bridge Fair. This attracted between 200 and 300 people. The bride’s dowry was reported as being the very substantial sum of £500, together with a furnished caravan.[23] Such large weddings tended to occur where substantial Gypsy gatherings were already taking place, for instance coinciding with horse fairs or race meetings.[24] A slightly more low-key event was reported at Bourne, where a Gypsy wedding took place in 1853 between two parties who were ‘advanced in years’. This was ‘kept in the usual manner with fiddling, dancing etc.’.[25]

Gypsies in Unexpected Places: Towns and War

The evocation of bucolic roaming in the picturesque countryside did not capture the complexity of the lives of Lincolnshire’s Gypsies. Nor did the popular image associate them with towns and cities, yet they did engage with urban life.

George Hall recounts an early childhood memory of Lincoln, in the shadow of the Cathedral:

Not far from my father’s doorstep, as you looked towards the common, lay a narrow court lined with poor tenements, and terminating in a bare yard bounded by a squat wall … somewhere in the fifties of the last century [ie in the 1850s] several families of dark-featured “travellers” had pitched upon the court for their Gypsyry, a proceeding at which our quiet lane first shrugged its shoulders, then focussed an interested gaze upon the intruders and their ways, and finally lapsed into an indulgent toleration of them. Thus from day to day throughout my early years, there might have been seen emerging from the recesses of Gypsy Court swarthy men in twos and threes accompanied by the poacher’s useful lurcher… [26]

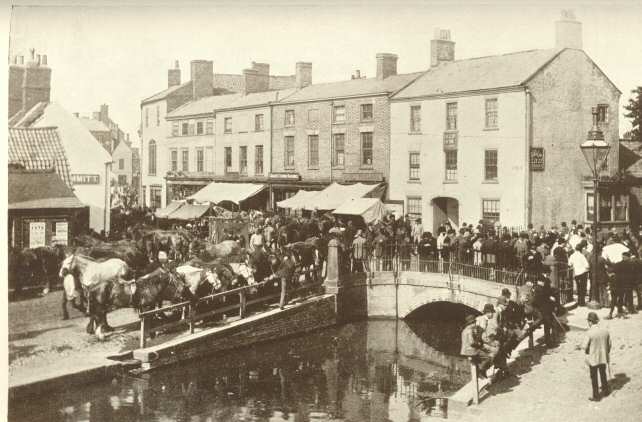

Gypsy horse dealers played a prominent part in the county’s horse fairs, especially at the annual events at Lincoln in April and at Horncastle in August. In April 1864, for instance, the Stamford Mercury observed that at Lincoln, in advance of the fair, there were pitched tents and ‘many

caravans belonging to the wandering Bohemians’.[27] In August 1885, the Lincolnshire Chronicle reported that at Horncastle horse fair ‘the gipsy fraternity was largely represented’.[28] In most years, the Gypsies’ presence at fair time was evidenced through later court appearances, often for drunkenness, fighting and cruelty to horses. Many other residents and visitors engaged in such activities, but care was taken in the newspaper reports to highlight which defendants were Gypsies.

In addition to Gypsies’ periodic harassment from residents as they travelled their regular circuits, they were also exposed to unwelcome officialdom in towns, as urban spaces became increasingly regulated by the end of the nineteenth century. In 1899, for instance, it was reported that in Lincoln, where there were ‘occasional encampments of gipsies on vacant ground on Monks Road’, the city’s Inspector of Nuisances was ‘to inspect the gipsies and their caravans’.[29]

Thousands of men from the UK’s Gypsy communities served their country in the two world wars (contrary to the stereotype that they evaded conscription by fleeing to Ireland). Nineteen-year-old Gypsy John Cunningham of Scunthorpe won the Victoria Cross in 1916 for his bravery at the Battle of the Somme, for example; a stone was laid in his memory at the Remembrance Day service in 2016.[30]

This brief account has sought to demonstrate that Gypsy people do inhabit the many documentary sources of Lincolnshire’s past, although not in their own words. However, if treated carefully, these sources can be read against the grain to understand both the ways in which Gypsies were perceived and treated and to some extent also their own agency and attitudes. The point is that there are considerable challenges in retrieving and understanding the past lives of the county’s Gypsy communities, but these are by no means insuperable.[31]

Andrew Walker is a historian of Lincolnshire. He worked at the University of Lincoln from 1992 to 2010, latterly as Head of the School of Humanities and Performing Arts. Between 2010 and 2020, Andrew was Vice Principal of Rose Bruford College. He is an active volunteer researcher for Reimagining Lincolnshire.

Notes

[1] Lincolnshire Chronicle, 3 July 1840.

[2] Lincoln Gazette, 27 June 1874.

[3] Lincolnshire Chronicle, 22 May 1846.

[4] See for instance reports in Lincoln Gazette, 27 June 1874 and Lincolnshire Free Press, 8 February 1876.

[5] Louth & North Lincolnshire Advertiser, 26 October 1861.

[6] Lincolnshire Free Press, 8 February 1876.

[7] Lincolnshire Chronicle, 23 June 1854.

[8] Lincolnshire Chronicle, 16 November 1883.

[9] Louth Standard, 30 June 1928.

[10] Lincolnshire Free Press, 9 April 1889.

[11] Lincolnshire Chronicle, 16 November 1883.

[12] Stamford Mercury, 29 May 1857. This report was widely reprinted in papers ranging from the Edinburgh Evening Courant, 4 June 1857 to the Dover Telegraph, 6 June 1857. See also the Illustrated London News, 6 June 1857.

[13] Grantham Journal, 13 May 1922.

[14] Sleaford Gazette, 8 December 1939.

[15] Searchable online copies of the Journal of the Gypsy Lore Society can be found at www.catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/000499763 [accessed 13 June 2022].

[16] Stamford Mercury, 1 May 1874. The report was extracted from the Saturday Review.

[17] For more information on the Gypsy Lore Society, see Harte, ‘”On the far side of the hedge”’, 31-2 and, for a more critical interpretation, see Becky Taylor and John Hinks, ‘What field?’, 632.

[18] Grantham Journal, 18 August 1855.

[19] Lincolnshire Chronicle, 11 August 1893.

[20] Grantham Journal, 1 March 1890.

[21] Grantham Journal, 6 September 1856.

[22] Louth & North Lincolnshire Advertiser, 28 May 1864.

[23] Stamford Mercury, 12 October 1888.

[24] Grantham Journal, 17 June 1882.

[25] Lincolnshire Chronicle, 9 September 1853.

[26] George Hall, The Gypsy’s Parson: His Experiences and Adventures. (London, 1915), 2.

[27] Stamford Mercury, 29 April 1864.

[28] Lincolnshire Chronicle, 14 August 1885. For more information on Horncastle Fair and Lincoln’s April Fair, see respectively B.J. Davey, Lawless and Immoral: Policing a Country Town, 1838-57 (Leicester, 1983) and Andrew Walker, ‘Fairs and markets: challenging encounters between the urban and rural in Lincolnshire, c.1840-1920’, in Shirley Brook et al., eds, Lincoln Connections: Aspects of City and County Since 1700. A Tribute to Dennis Mills (Lincoln, 2011), 107-23.

[29] Lincolnshire Echo, 29 July 1899.

[30] Cunningham’s story is at https://www.travellerstimes.org.uk/news/2016/11/gypsy-first-world-war-hero-honoured-scunthorpe [accessed 18 June 2022].

[31] A number of holdings can be found relating to British gypsy, traveller and Roma heritage, for instance, at the University of Liverpool, where the archive of the Gypsy Lore Society is stored. See www.libguides.liverpool.ac.uk/library/sca/gypsyloresociety [accessed 15 June 2022]. Extensive Gypsy, Traveller and Roma Collections are available at the University of Leeds. See www.library.leeds.ac.uk/special-collections/collection/702 [accessed 15 June 2022]. See also the Robert Dawson Romany Collection at the Museum of English Rural Life, Reading at www.merl.reading.ac.uk/collections/robert-dawson-romany-collection/ [accessed 15 June 2022]