Hope Williard

Women in Ancient Roman society have been largely marginal in historical studies of the period, even though they were citizens. Unable to vote or hold office, they did nonetheless exercise agency and influence within the private sphere. Of course, enslaved women and those of a lower social status have featured even less in the historical record.

This blog post travels back in time to the period between the mid-first and the early fifth centuries CE, when Lincoln was the Roman city of Lindum Colonia. Today, we can still see an impressive array of remains, especially of the city walls and gates, all around the city. If you are starting from the lower city and are willing to brave the aptly-named Steep Hill, walking a loop of the visible remains of Roman Lincoln takes approximately two hours. This post will introduce you to two of the women you might have met walking that same loop hundreds of years ago.

As you will see, they hidden are in plain sight.

Introducing Lindum Colonia

Roman presence in what is now Lincolnshire began well before the conquest of Britain in the year 43 CE. The Roman conquest of Gaul (modern-day France) during the 50s BCE included a brief military incursion into Britain, under the leadership of Julius Cesar, in 55 and 54 BCE, and led to increasing economic, political, and cultural contact. Like other groups on the empire’s borders, the peoples of south-eastern Britain had economic contact with the Roman world for decades before invasion, through trade in iron, salt, agricultural goods, and enslaved people. Empires cultivate and exploit areas beyond their borders for their human and economic capital, but we can also see the peoples of Britain pursuing the economic, political, and cultural assets of contact with their powerful neighbour in support of their own aims.

In approximately 47 CE, Roman forces (specifically, IX Legion Hispana) first reached Lincolnshire and established a series of short-term military camps. A more permanent military presence in the region dates to several decades later–the first stages of Roman fortifications in Lincoln seem to date to the 60s and 70s CE, with the presence of the ninth and then the second legions in the area. The next stage of Roman Lincoln’s development was as a colonia (from which we get the English word colony) the highest status of Roman city.

While the precise date of foundation of the colonia is not entirely clear, archaeologists estimate that it was between 84 and 96 CE, during the reign of the emperor Domitian. The city retained links to its military origins. During this period, the Roman state granted legionaries who had finished their period of service lands in coloniae across the empire. Veterans were permitted to retire to areas where they had served with the expectation that their sons would grow up to become future legionaries. The wooden buildings and walls of the early military occupation were replaced with stone and over the next few centuries Roman Lincoln expanded, eventually coming to have a distinctive presence in the uphill and downhill areas of the modern city of Lincoln.

Lucius Septimius Severus was Roman emperor from 193 to 211. Born in Leptis Magna in North Africa, Severus was the first African-born Emperor of the Roman Empire. His wife, Julia Domna was a Syrian Arab woman who exerted power and influence, accompanying Severus on military campaigns, mediating between her sons and influencing literary and artistic works.

Septimius Severus ordered that Lindum Colonia should have proper stone walls to replace the wooden ones of the early military occupation. For a few years, Septimius Severus ran the whole of his Empire from Eboracum – today’s York. There were other wealthy citizens of African heritage in Eboracum. We know that there were also people of African heritage living in Lindum Colonia. The evidence is from the human remains that archaeologists found on the route of the new Eastern bypass around Lincoln.

The population of Roman Lincoln varied over the course of its history, from perhaps 5,000 during its early days to as many as 10,000-12,000 at its height, making it a moderately sized but not especially big city by the standards of Roman Britain. The city brought together people of a range of different origins and backgrounds. Native British and immigrant craftspeople, local traders and merchants from far afield, government officials, soldiers and ex-soldiers and visitors or emigrants from rural areas, were just some of the many people who lived in or had connections to the colonia over its four centuries of history. Through the evidence of the city’s material culture, and particularly its tombstones, we can meet its inhabitants.

Meet Claudia Crysis

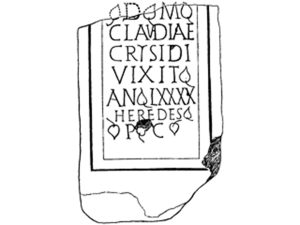

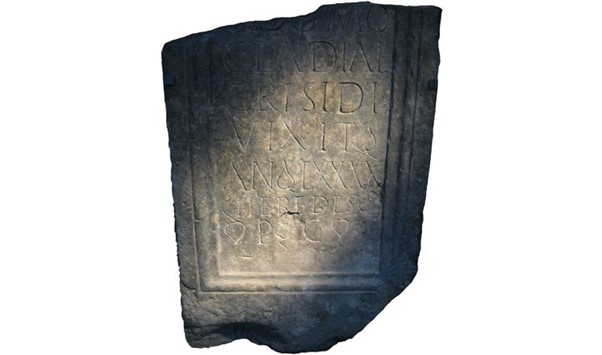

The tombstone of Claudia Crysis reads:

To the spirits of the departed (and) to Claudia Crysis; she lived 90 years. Her heirs had this set up.

Ninety is an impressive age in any era and Claudia is currently the oldest woman we know of from Roman Britain. Her brief epitaph, which may date from the second century, was discovered on Lindum Road in 1830, having been built into the east wall of the lower city sometime during the fourth century.

Her second name, crysis, possibly indicates that she had blond hair. The tombstone does not allow us to say anything about her family background or origins. Funerary inscriptions sometimes, but not always, name the person who was responsible for the monument being set up and specify their relationship to the deceased, but Claudia’s heirs chose not to identify themselves by name. Whether this came from an unwillingness to pay for the extra lines on a larger stone, deference to Claudia’s own wishes, or self-effacement on their part, is impossible to say. Although the inscription is brief and nothing else is known about her, her epitaph nonetheless invites us to learn more about Roman experiences of age and aging.

A common misconception about the ancient and medieval worlds is that everyone died young. Demography – the statistical study of population structures – is one of the tools scholars use to draw conclusions about issues like infant mortality and life expectancies in the ancient world. This can come from two sources: analysis of human remains to determine someone’s approximate age at death, and Roman tombstones, which frequently say how old a person was when they died. Due to extremely highly mortality rates among infants and children, the rough average life expectancy was somewhere between twenty and thirty. To compensate for the effects of child mortality on this average, scholars use a method known as model life tables to estimate the proportion of the population in certain age groups. For instance, someone who survived past the age of ten was, on average, likely to live into their late forties; a person who made it to the age of sixty could expect to live for approximately another decade. Demographers have estimated that around six to eight percent of the Roman population was elderly. While this is a lower proportion than in our own society, it suggests that most people would have known older people in their families or social circles.

Based on the evidence provided by their law and literature, Romans regarded sixty as the onset of old age for men. There is some evidence that this varied by occupation: during the Roman Republic the normal age that a man might be expected to perform military service was between the ages of sixteen and forty-six. However, the arrangements made for the settlement of veterans on land around the empire after their period of service had finished indicates that they were clearly expected to have a reasonable span of active years left to them after retirement. For women, it seems that the beginning of old age was associated with the onset of menopause or between the ages of forty and fifty. For both men and women, the onset of old age was strongly identified with its effects on the body and mind, rather than their calendar age.

While Romans did celebrate their birthdays, an individual’s exact knowledge of their own age was likely to depend on their circumstances. For example, someone who had received at least some education, or who had strong family or social networks, was more likely to be able to accurately gauge their own age. Uncertainty or best guesses about age also applied to tombstones, where it was common to round to the nearest five or nearest ten, suggesting that Claudia Crysis may not have been exactly ninety years old when she died.

Whether she was in her late eighties or early nineties, Claudia stands out in more ways than one. She would have had very few peers in Roman Britain–her tombstone is our only epigraphic evidence of a nonagenarian woman. Possibly the next oldest woman in Roman Britain, Julia Secundina, lived to be seventy-five; she was buried at Carleon with her husband, the legionary Julius Valens, whose tombstone marks him as one of the Roman world’s rare centenarians. Furthermore, the lettering on Claudia’s monument is extremely well cut, indicating that she and her heirs were able to afford a high-quality memorial. This, combined with her advanced age, suggests that she had the wealth and social standing to access the higher standard of living which enabled her to lead such an extraordinarily long life.

Meet Carssouna

Once they had outlived their function as memorials, Roman tombstones were often reused as building materials. (This is how Claudia Crysis’ tombstone ended up being removed from a cemetery and built into a late Roman wall.) The next time you are on your way to Lincoln train station, pause in front of the west tower of the church of St Mary Le Wigford, and look to the right of the doorway.

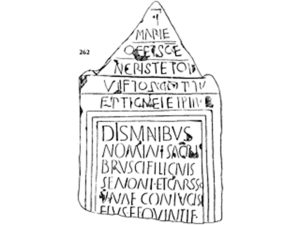

You will see a fragmentary funerary inscription built into the church itself. The inscription was first recorded by the Lincolnshire antiquarian, physician, and clergyman, William Stukeley, in 1722, as part of his lifelong efforts to document and explore Britain’s Roman past. The church itself dates to the late tenth century but what you can see today is newer than this–the tower itself was built in the late eleventh century. The inscription itself seems to have been added at the time the tower was built and to have been in place ever since.

Fascinatingly, it comes in two parts. The lower part is a Latin inscription, which reads in translation:

To the departed spirits (and) to the name of Sacer, son of Bruscus, a citizen of the Senones, and of Carssouna, his wife, and of Quintus, his son…

The bottom edge of the stone is broken off and the inscription appears to be incomplete. If another few lines were present, they may have identified the person who was responsible for setting up the memorial. Carssouna, her father-in-law Bruscus, husband Sacer, and son Quintus provide a very interesting example of three generations of a Roman-British family. The description of Bruscus as ‘a citizen of the Senones’, would indicate that he had come from Gaul (specifically, the area around the city of Sens) to Lincoln. It is a lovely example of how people from outside Lincolnshire have long been a part of its history.

In a world without birth certificates or passports, someone’s name declared their identity and origins, so it is worth considering these names in more detail. They show interesting changes across the generations. Both Bruscus and Sacer have names which echoes the forms of Latin names, even if they are not entirely Roman. However, the youngest generation on the tombstone, Quintus, has an extremely common Roman name. Perhaps his parents hoped he might grow up to be someone who made a place for himself in the wider Roman world? Carssouna stands out on the tombstone just only as the only woman to be mentioned, but also for her distinctly non-Roman name. Unlike the name Quintus, Carssouna is an incredibly rare name, and raises intriguing questions. We might imagine her parents choose a culturally resonant name out of pride in their heritage, much the way that parents might do today.

We would not necessarily know about Carssouna at all if the stone had not been reused for a later inscription. The individual who commissioned and funded the building of the eleventh century tower where the stone resides today, commemorated his deed in an Old English inscription which reads:

E[i]rtig had me built and endowed to the glory of Christ and Saint Mary, ☧.

The inscription is crammed into the pediment of the old Roman tombstone. It is right side up but slightly confusing in that it is read from bottom to top. Unlike the reuse of Claudia’s tombstone as building materials, this shows a more dynamic engagement with Lincoln’s Roman past. Although both inscriptions are now quite weathered, they would have been plainly visible to viewers, and Ertig himself or other viewers may have seen a connection between the two inscriptions. One theory is that the stone was reused due to a misreading of the words nomini Sacri–‘to the name of Sacer’–as a Christian message about the sacred name of the divine. But then why was the rest of the text, which has no such ambiguities, so prominently displayed? While the full story of the inscription remains a mystery, we can be grateful it left one of Roman Lincoln’s women hidden in plain sight.

Further Reading

Lindsay Allison-Jones, ‘The Family in Roman Britain’ in A Companion to Roman Britain ed. Martin Todd (Oxford, 2004), pp. 273-287.

Charlotte E. Bell, ‘The Autonomy of Power: Epigraphy of Women in Roman Britain’ (MA Dissertation, University of Liverpool, 2020).

Karen Cockayne, Experiencing Old Age in Ancient Rome (London: Routledge, 2003).

Guy De la Bédoyère, The Real Lives of Roman Britain (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015).

Andrew C. Johnson, The Sons of Remus: Identity in Roman Gaul and Spain (London, 2017).

Michael J. Jones, Roman Lincoln: Conquest, Colony, and Capital (Stroud, 2011).

Anthony Lee (2013) Claudia Crysis – Roman Britain’s oldest woman. [blog] The Collection. Available at: https://www.thecollectionmuseum.com/?/blog/view/claudia-crysis-roman-britains-oldest-woman [Accessed 23 March 2022].

–Treasures of Roman Lincolnshire (Stroud, 2016).

–(2016) Roman Lincolnshire in the British Museum. [blog] Roman Lincolnshire Revealed. Available at: https://romanlincolnshire.wordpress.com/2016/09/30/roman-lincolnshire-british-museum/ [Accessed 23 March 2022].

–(2018) Some women of Roman Lincolnshire. [blog] Roman Lincolnshire Revealed. Available at: https://romanlincolnshire.wordpress.com/2018/03/08/some-women-of-roman-lincolnshire/ [Accessed 23 March 2022].