The first Black History Trail ever in the city of Lincoln has been designed by researchers of Reimagining Lincolnshire, a public history project based at the University. It aims to expand our appreciation of the city’s diverse heritage and how we have been shaped by the mobility of people, goods and ideas over the centuries. From African Roman Emperor Septimius Severus to the Caribbean RAF veterans who resided here during World War 2, black people have been part of the everyday fabric of the city. Some have made extraordinary contributions. The trail focuses on Lincoln but will make connections to the region and the wider world.

The trail starts at the intersection of the High Street and Wigford Way and ends at the Cathedral. There are eight stops altogether. This blogpost is set out in the same order as the trail, so that it’s easy to find further information related to each stop.

Stop 1: St Mary le Wigford[1]

We’ll tell stories here about army veterans, industrial workers and football players.

Ann Bishop, a Lincoln woman, was buried at St Mary le Wigford in 1826. She was 36 years old. (The churchyard has now disappeared under urban development.) She was married to Peter Bishop, a black man who was born in Barbados in 1792. He enlisted in the 2nd Battalion of the 69th (South Lincolnshire) Regiment of Foot in 1806 and subsequently moved to Lincoln with his Battalion. Whether he was free or enslaved prior to enlistment is unknown. He and Ann were married in 1810.

In the 18th and early 19th centuries, black soldiers served in many regiments of the British army as military musicians, specifically drummers. Racialised beliefs at the time stereotyped black people as having a propensity for music and their presence in regiments was considered a sign of military prestige.

Regiments often put on parades in which all their musical resources would be focused on promoting regimental image in the hope of ingratiating the regiment with local worthies, or, more seriously as far as the survival of the regiment was concerned, to aid recruitment. [2]

Peter Bishop was such a drummer and his duty was to beat out the drum patterns issued by his commanders to communicate orders to the soldiers. He was soon off to war again and served at the Battle of Waterloo. He survived the horrific conditions and received the Waterloo Medal. After this he seems to have been discharged. Like many other veterans of the time, Peter and Ann experienced homelessness and spent the rest of their lives in and out of Lincoln’s workhouse. After Ann’s death, Peter remarried but continued to face poverty until his own death at the age of 65. He is buried in uphill Lincoln, in what would have been the grounds of the Union Workhouse. There were probably several other black army veterans like him, living in Lincoln in the late 18th and early 19th centuries[3].

Along the end of Wigford Way is the Lincoln site of Siemens, the current-day company that started life as Ruston’s, and a reminder of a long history of heavy engineering in the city. Ruston’s and others such as Fosters, Clayton and Shuttleworth and Robeys, produced agri-machinery, excavators, engines, cranes, tanks and planes. These machines were exported all over the British Empire and beyond. These goods and the people that made and used them are connected to the vast history of Britain’s imperial expansion.

Ruston’s was one of the most prolific Lincoln-based companies and their products were exported to places like Africa and the Caribbean. One could find a Ruston’s saw mill in Senegal, diesel engines and excavator mines in Togo and trains in Ghana[4]. This also meant that trainee engineers and workers from Africa and the Caribbean would regularly come to visit Lincoln’s factories to learn how to maintain these goods[5]. Public history tends to remember the people who invented, designed or owned objects. Much less credence is given to those who made them and kept them going.

Beyond St Mary le Wigford to the south is Sincil Bank, Lincoln City FC’s ground. Lincoln City was the first club in the English league to hire two black players, in 1899 and in 1909.

Johnnie Walker was the first black footballer to play in the Scottish league. Lincoln signed him in 1899 for £25 and he became the first black player to command a transfer fee in the UK[6]. Guyanese player Willie Clarke was the first black player to score in the English league for Aston Villa in 1901. He transferred to Lincoln from 1909-1912[7]. In more recent times, former English League and international player Keith Alexander became manager of LCFC in 1993, only the second black manager in the English league (after Tony Collins at Rochdale in 1960). He later became the first qualified black referee[8].

The Reimagining Lincolnshire project has uncovered another black player as early as 1903 – a goalkeeper for Lincoln Liberal Club[9]. We have yet to discover more about his identity.

Stop 2: Cornhill[10]

Lincoln has various connections with transatlantic slavery. Cornhill is particularly associated with the abolitionist movement and other global movements for social reform.

The transatlantic slave trade was the enforced and violent removal of over 12 million people from Africa from the 16th to the 19th centuries. Most Western European powers participated in and benefited from this trade. We know of several Lincoln residents who were ‘compensated’ for the loss of enslaved labour when slavery was abolished in the British Empire in the 1830s. Margaret Ashton, wife of a mason, lived in Newport and owned a plantation in Jamaica; Harman Dwarris likewise lived in Lincoln and owned a Jamaican plantation and 18 enslaved people. These examples remind us that townspeople benefited from the system, as well as those with country estates[11].

There was also a strong abolitionist movement in Lincoln. Women and children across Lincolnshire protested against slavery through boycotting sugar, one of the most lucrative crops grown on the plantations. In one account of a meeting, women ‘were pierced to the heart with the sufferings of the oppressed Africans; and with a fortitude which does them the highest honour, refused to enjoy those sweets, which they supposed to be the price of bIood.’ (Mark Jones 1998: 63)[12]

The movement for abolition continued until slavery was ended after the American Civil War in 1865. Several formerly enslaved people visited Lincoln and addressed huge audiences at Cornhill. Isaac Dikerson, also a war veteran and member of the famous Fisk Jubilee Singers, spoke here in 1894[13]. In the video below you can listen to the earliest known recording of the Fisk Jubilee Singers in 1909. Courtesy of Nathaniel Jordan on YouTube.

The movement for abolition was strongly connected to two other global campaigns for social reform, temperance (the trades in people and alcohol were closely connected) and women’s rights. Rev. John Henry Hector, the so-called ‘Black Knight of the Temperance movement’ addressed the crowds here in 1895 and 1897. Hallie Quinn Brown, a university-educated orator and women’s rights campaigner, spoke here in 1895[14]. Preacher Benjamin William Brown spoke at Cornhill in 1897[15].

Objects from the past tell the story of slavery and abolition, too. Sugar was the hedonic that stimulated the mass consumption of other hedonics like chocolate, coffee and tea. The Usher Gallery has an example of a tea, coffee and chocolate set – cups and saucers, pots, jugs, bowls and tray – that were produced to cater to changing habits and fashions in entertaining. The Gallery also holds a late 18th century Wedgwood trinket box displaying the symbol of the abolitionist movement in Britain: a kneeling enslaved man with his manacled arms stretched out before him, as if begging for freedom. This symbol has long attracted criticism for denying the agency of the enslaved themselves in struggling for their freedom[16].

Stop 3: High Street Waterside[17]

Street scenes of this part of the High Street in the 1860s reveal that black people were an everyday presence[18].

During World War 2, there was an influx of personnel from all over the world. Lincolnshire mostly housed RAF stations (although there were some army units here too). Among those who came to serve in the RAF were over 5,000 black Caribbean ground personnel. Many would have come into Lincoln when off duty, to cinemas, dancehalls and the NAAFI[19].

The building above Waterstone’s was then a popular gathering place for RAF officers – the Saracen’s Head. One of them was Billy Strachan, one of the very few black pilots to serve in RAF Bomber Command. Born in Jamaica, he sold his possession and made his way to the UK in 1940. On arrival, he took and passed the Air Ministry tests and trained as a wireless operator. He excelled as a wireless operator, completing over 30 operations in enemy territory. He then trained as a pilot and was based at RAF Fiskerton. Popular with his crew, he always managed to get them home safely. Yet one night, taking off from Fiskerton, he asked his engineer for the location of Lincoln Cathedral’s spire.

In his own words Strachan recalled the incident: “He replied, ‘We are just passing it.’ I looked out, shocked that the spire was not where I expected, below us, but just a very few feet beyond our wingtip. I hadn’t seen the spire at all — and I was the pilot!” He flew out over the north sea, ditched the whole bomb load and returned to Fiskerton. He never flew after that. After the war, he trained as a lawyer and co-founded the Movement for Colonial Freedom. He became a very prominent anti-racist campaigner. He died in 1998[20].

Stop 4: Stonebow[21]

The Stonebow Guildhall has been the civic centre of Lincoln since the 1300s and is the seat of the City Council.

Ralph Toofany was a nurse who came to Lincoln from Mauritius. He was one of the thousands of Caribbean, African and Asian nurses, doctors and other healthcare workers who migrated to the UK to staff the new NHS after 1948, and have been the rock of the NHS in Lincolnshire ever since.

Ralph worked at St John’s psychiatric hospital in Lincoln. In common with many psychiatric hospitals St John’s was a major employer of black and Asian workers. He was also a trade unionist and Labour Party activist. He became Lincoln’s first black councillor, first black mayor (in 1992) and later Lincoln’s first black Sheriff. He was still serving in the council when he helped to build Lincoln’s Central Mosque, which opened in Boultham in 2018[22].

Other notable people of colour in Lincoln’s civic life include first Sikh Sheriff, Jasmit Kaur Phull and Gregory Yeargood, RAF veteran and mace-bearer in the 1990s[23].

For a time after World War 2, Lincoln City Council was twinned with the city of Pietermaritzburg in South Africa. Pietermartizburg gifted to Lincoln a ceremonial rug crafted by black women in the township of Sobantu, a segregated part of Pietermaritzburg. Lincoln named some streets after residential areas in Pietermaritzburg, such as Edendale[24].

At this time, South Africa had an apartheid regime where discrimination against people based on their skin colour was violently enforced by the state. Only white people therefore tended to benefit from the twinning arrangement. In the 1960s, Lincoln anti-apartheid activists called for an end to the connection and it petered out[25].

Stop 5: Clasketgate[26]

It’s fitting that we use the site of one of Lincoln’s oldest theatres, the Theatre Royal, to tell the story of the long association of black entertainers with Lincoln.

Ira Aldridge was a famed Shakesperean actor of the 19th century. He was born in New York in 1806 and began his acting career there, but came to the UK with a friend in the 1820s, tired of the racism he encountered in the US[27]. In 1842 and 1849, Aldridge played at the Theatre Royal. According to the review in the Lincoln Standard, ‘his talents are first rate, and his conduct gentlemanly, strongly evidencing that mankind all have an equal capacity, if they had but the opportunity of receiving instruction’[28].

Other black entertainers to appear in Lincoln in the 19th century included Carlos Trower, a tight rope walker, who thrilled crowds in Lincoln in the 1860s[29]. Delmonico, described as ‘a man of colour’ and ‘daring performer’, appeared with lions and tigers at Lincoln’s April Fair in 1870[30].

One hundred years later, 1960s Mod culture was heavily influenced by postwar African American Chuck Berry, the father of rock and roll and singer of Maybelline played at Lincoln’s ABC cinema in 1965[31]. Jimi Hendrix, the world’s greatest guitar player, played there too in 1967[32]. However, a far more famous music venue in Lincolnshire was the Gliderdrome in Boston, where Hendrix also played. Others included Otis Redding, The Equals and Tina Turner[33].

The first film shot on location in Lincoln was The Wild and the Willing, in the early 1960s. It was about student life in a fictional university town called Killminster. Stars Ian McShane, John Hurt, and Samantha Eggar all debuted in the movie[34]. It also starred Johnny Sekka, an African actor from Dakar in Senegal. He had worked in the docks in Banjul, where he stowed away on a ship to Europe. In the 1950s he joined the RAF and started acting as a hobby. A big talent, his breakthrough came in 1959 when he starred in a stage version of the Joyce Carey novel, Mister Johnson. He went on to play roles with some of Britain’s most notable actors, such as Laurence Olivier and Orson Welles[35].

Stop 6: Steep Hill[36]

This stop focuses on the story two thousand years ago: Roman Lincoln’s African connections

This city’s connection with the Roman Empire began in around CE60, when the Ninth Legion built a fort here for around 5,000 legionaries. It was then abandoned as the army moved north. In the late first century CE, a colonia was founded on the same site. A colonia was a self-governing city of the highest status, meant to be a model of Roman civilisation. This one was called Lindum Colonia, which over time was shortened to Lincoln. Its first settlers were retired legionaries. It was one of only four such settlements in the whole of Britain and remained a colonia until the fall of the western Roman Empire in the fifth century CE. The colonia’s wealthy citizens contributed to the development and beautification of the urban environment[37].

Septimius Severus was the first African-born Emperor of Rome. He was born in Leptis Magna in North Africa, which today is the city of Khoms in Libya. It was Severus who, in the late first century CE, ordered that Lindum Colonia should have stone walls to replace the old wooden fortifications. That we can still see remains of walls and gates, connecting us with our Roman past, is therefore due to Severus. For a few years, he made Eboracum (today’s York) his headquarters. He died there in CE 211. Severus’s original walls and gates were enlarged on numerous occasions, although in Roman times, the colonia was never subjected to attack. Construction was more for ceremonial splendour[38].

We know that there were also people of African heritage living in Roman Lincoln. One form of evidence is the DNA tests conducted on the human remains that archaeologists found on the route of the new Eastern bypass around the city[39].

Stop 7: Castle Hill[40]

We have demonstrated how the coming and going of people to and from Lincoln to the Americas, Asia and Africa and vice versa has been common through the centuries. Black people far before the Windrush (post-1950s generation) spent all their lives or large part of their lives in Lincoln. One such person was Francis Barber in the 1750s[41].

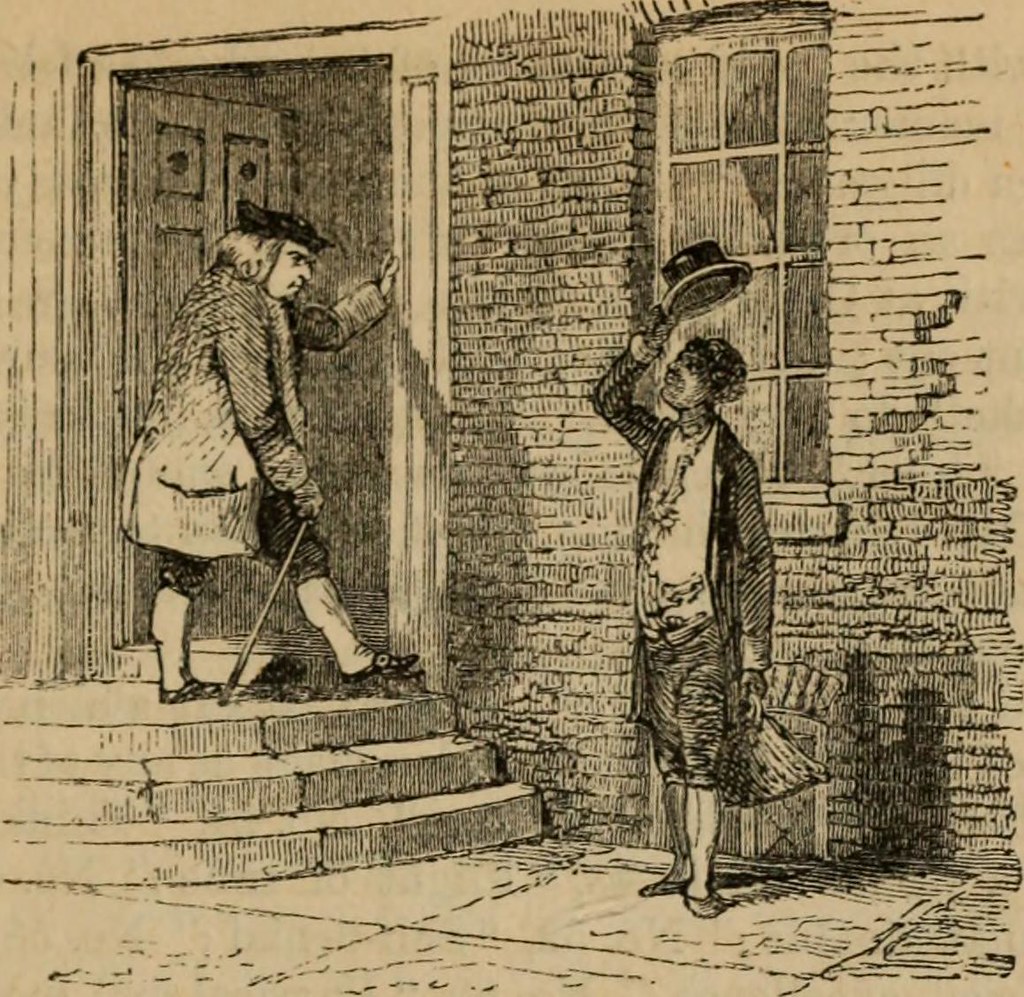

Francis Barber was born into slavery. Colonel Richard Bathurst was the owner of the Orange River Estate where Barber was born. This plantation was one of the largest sugar plantations in Jamaica. Bathurst had strong ties to Lincolnshire and owned a home in Lincoln in The Close. In the 1750s he returned to Lincoln with Francis Barber who was seven years old at the time. There is some evidence that he was baptised here, at St Mary Magdalene Church.

Bathurst sent Barber to boarding school in Yorkshire. In his will in 1754, he ended Barber’s enslavement. Francis Barber joined Samuel Johnson’s household as a high-ranking servant. Johnson was a famous writer and the compiler of the first English dictionary. Barber continued to work for Johnson until Johnson’s death in 1784. Barber was at his side even at death and was a beneficiary of Johnson’s will. Francis Barber and his wife Elizabeth and their children then moved to Lichfield in Staffordshire. There they faced much hardship, but Barber died in 1801 as a free man.

This Image is of Francis Barber and Samuel Johnson from page 220 of “The life of Samuel Johnson, LL.D., comprehending an account of his studies and numerous works, in chronological order; a series of his epistolary correspondence and conversations with many eminent persons” (1859) . Courtesy of Internet Archive Book Image on Flickr (Public Domain).

Stop 8: Cathedral[42]

The cathedral contains several objects related to British settlement, exploration and empire.

The cathedral library contains the so-called Massachusett Bible, the first Bible to be published in an indigenous language in British North America. Puritan missionary John Eliot translated the Bible into the Wôpanâak language in 1663[43]. The Wôpanâak language subsequently disappeared due to colonial expansion and violence. The Eliot Bible has recently become instrumental therefore, in assisting Wôpanâak people to relearn their language.

The St. Blaise chapel contains a painting of Jamaican World War 2 veteran Patrick Nelson. Duncan Grant, a member of the Bloomsbury Group, was commissioned to paint the mural which he completed in the 1950s. Patrick Nelson and Duncan Grant met in the late 1930s when Nelson had moved to London to study law, funded by working as an artist’s model[44]. They had a romantic relationship and Grant wrote to Nelson when he was captured as a prisoner of war during his service in the British Expeditionary Force. The painting of Nelson is problematic as it fetishizes the black male body. However, the cathedral hid the mural away for many years for a different reason: Grant used as models several others, men and women, with whom he had complex sexual relationships[45].

There is a sculpture of Nelson Mandela’s head on the southwest turret of Lincoln Cathedral, installed after his death in 2013. It is sited next to the stone head of an unknown African man[46].

[1]Location of St. Mary Le Wigford, 3 St Mary’s St, Lincoln LN5 7AR, https://goo.gl/maps/2tXZ9RaNMv3Kkc5s7

[2] John Ellis, Drummers for the Devil? The Black Soldiers of the 29th (Worcestershire) Regiment of Foot, 1759-1843. Journal for the Society of Army Historical Research 80, 323, 2002, p. 193

[3] For more information on Pete Bishop see John D. Ellis, ‘Peter Bishop, 1792-1851: Soldier of the 69th Foot and Veteran of Waterloo’ at https://www.historycalroots.com/peter-bishop-1792-1852-soldier-of-the-69th-foot-and-veteran-of-waterloo/. The HistorycalRoots blog also has a wealth of information about other black veterans of the time.

[4] Bernard Newman, One hundred years of good company. Gateshead on Tyne, Northumberland Press, 1957.

[5] Imagery of Ruston & Hornsby Engine Assembly Works from c. 1945. John Wilson Collection, Saxilby History Group.

[6] For more information on Johnnie Walker see Andy Mitchell, ‘John Walker, a black professional in the Scottish and English Leagues’ at https://www.scottishsporthistory.com/sports-history-news-and-blog/john-walker-a-black-professional-in-the-scottish-and-english-leagues

[7] For more information on Willie Clarke see Andy Mitchell, ‘Willie Clarke – Scotland’s second black internationalist’ at https://www.scottishsporthistory.com/sports-history-news-and-blog/willie-clarke-scotlands-second-black-internationalist

[8] For more information on Keith Alexander see Paul Elliot, ‘Keith Alexander was a true pioneer in the fight for racial equality’ at https://www.theguardian.com/football/blog/2010/mar/03/keith-alexander-macclesfield

[9] Lincolnshire chronicle, 25 September 1903

[10]Location of Cornhill, 1, Exchange Arcade, Lincoln LN5 7HJ, https://goo.gl/maps/rtqhBEynTEUqHaP97

[11] UCL Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slavery, Database. https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/search/

[12] Mark Jones, The mobilisation of public opinion against the slave trade and slavery : popular abolitionism in national and regional politics, 1787-1838. PhD thesis, University of York, 1998.

[13] Based on data collected from Lincolnshire-based newspapers digitised in the British Newspaper Archive from 1837 onwards including: Boston Guardian (wkly), Grantham Journal (wkly), Grimsby Daily Telegraph (daily), Horncastle News (wkly), Lincoln Gazette (wkly), Lincolnshire Chronicle, Lincolnshire Echo (daily), Lincolnshire Free Press (wkly) Lincolnshire Standard and Boston Guardian (wkly) Louth and North Lincolnshire Advertiser (wkly) Market Rasen Weekly Mail and Lincolnshire Advertiser (wkly) Scunthorpe Evening Telegraph (daily) Skegness Standard (wkly) Sleaford Gazette (wkly) Stamford Mercury (wkly)

[14] Ibid.

[15] For more information on Black Temperance campaigners see Jeffrey Green, ‘Black Temperance Campaigners in Late Victorian Britain’ at https://jeffreygreen.co.uk/129-black-temperance-campaigners-in-late-victorian-britain/

[16] The Collection and Usher Museums: https://www.thecollectionmuseum.com/

[17] Location of Lincoln High Street Waterside, 297A High St, Lincoln LN2 1AF, https://goo.gl/maps/ykC82vyjkLdBtV7f8

[18] Lincoln High Street scene, 1880s. Front cover of Maurice Hodson, Lincoln Then and Now, Volume III. M. B. Hudson, Lincoln.

[19] For more information about African Airmen in the RAF see Heather Hughes, ‘African Airmen in RAF Bomber Command’ at https://ibccdigitalarchive.blogs.lincoln.ac.uk/2017/10/24/african-airmen-in-raf-bomber-command/

[20] Frost, Peter, ‘Billy Strachan – just ‘another bloody immigrant’. The Morning Star, 2 April 2018

[21] Location of Stonebow, Guildhall Saltergate, Lincoln LN2 1DH: https://goo.gl/maps/GB79RcNqCrzsVuVS6

[22] Editorial in Lexpress.mu, 14 March 2006: https://www.lexpress.mu/article/mauritian-colony-united-kingdom-ii

[23] From the Stonebow Tour: https://www.visitlincoln.com/things-to-do/guildhall-and-stonebow

[24] From the British Pathé historical collection, ‘Lincoln Links Up With South Africa 1947’: https://www.britishpathe.com/video/lincoln-links-up-with-south-africa

[25] Roger Fieldfhouse, Anti-apartheid: A History of the Movement in Britain: a Study in Pressure Group Politics. Merlin, 2005.

[26] Location of Clasketgate, Lincoln LN2 1JJ: https://goo.gl/maps/EAGZHTMvB5JAXNvf6

[27] Folarin Shyllon, Black People in Britain 1555-1833, Institute of Race Relations, 1977.

[28] Lincoln Standard & General Advertiser 9 February 1842; Lincolnshire Times 30 January 1849

[29] Lincolnshire Chronicle, 23 November 1866

[30] For more information on black performers in Lincoln see Andrew Walker in the Reimagining Lincolnshire 2021 Heritage Open Days blog: https://reimagininglincs.blogs.lincoln.ac.uk/2021/09/23/unheard-voices-from-reimagining-lincolnshire/

[31]Chuck Berry 1965 UK Tour setlists are available at: https://www.setlist.fm/setlist/chuck-berry/1965/abc-cinema-lincoln-england-2bcd605a.html

[32] Interview with Jimi Hendrix, Lincolnshire Echo, 21 April 1967

[33] Jane Keightly 50 years of the Starlight Rooms at Boston Gliderdrome. Lincolnshire Life, April 2005. Available at: https://www.lincolnshirelife.co.uk/heritage/50-years-of-the-starlight-rooms-at-boston-gliderdrome/

[34] The Wild and the Willing (1962), British Film Institute database of films: https://www2.bfi.org.uk/films-tv-people/4ce2b6bad12ac

[35]Johnny Sekka Obituary, The Guardian, 29 September 2006: https://www.theguardian.com/news/2006/sep/29/guardianobituaries.artsobituaries2

[36] Location of Steep Hill, 50 Steep Hill, Lincoln LN2 1LT,https://goo.gl/maps/enKFuQrUbAeEZgRq5

[37] Michael J. Jones, Roman Lincoln: Conquest, Colony and Capital, The History Press, 2002. p. 34.

[38] Anthony R Birley, Septimius Severus: The African Emperor. London: Routledge, 1999.

[39] Ancient Burials and Artefacts unearthed beneath Lincoln Eastern Bypass Site, The Lincolnite, 17 February 2017: https://thelincolnite.co.uk/2017/02/ancient-burials-and-artefacts-unearthed-beneath-lincoln-eastern-bypass-site/

[40] Location of Castle Hill, St Mary Magdalene, Bailgate, Lincoln LN1 3AR, https://goo.gl/maps/mTL8xtErvggJMzM28

[41] For more information on Francis Barber see Heather Hughes ‘Francis Barber’s Lincolnshire Connections at: https://reimagininglincs.blogs.lincoln.ac.uk/2021/10/13/francis-barbers-lincolnshire-connections/

[42] Location of Lincoln Cathedral, Minster Yard, Lincoln LN2 1PX, https://goo.gl/maps/j3Jk6GFsKZM9NeVp7

[43] For more information on the links between Lincoln Cathedral and the USA see the Lincoln Cathedral Foundation website at: http://lincolncathedralfoundation.com/lincoln-and-the-usa/

[44] Gemma Romain, Race, Sexuality and Identity in Britain and Jamaica The Biography of Patrick Nelson, 1916-1963, Bloomsbury Press, 2017.

[45] For more information about Duncan Grant’s imagery of Patrick Nelson see Rianna Jade Parker ‘Black in Bloomsbury: What Duncan Grant’s Portrait of Patrick Nelson Reveals’ at:

https://www.frieze.com/article/black-bloomsbury-what-duncan-grants-portrait-patrick-nelson-reveals

[46]Lincoln Cathedral appeals for Publics Help to Raise 10K for Turret Restoration, The Lincolnite, 29 October, 2015: https://thelincolnite.co.uk/2015/10/lincoln-cathedral-appeals-for-publics-help-to-raise-10k-for-turret-restoration/

This walk is a wonderful outcome of the Reimagining Lincolnshire project. Well-researched, scholarly, and analysed with accuracy, acumen and commitment to the aims of the project overall. It is readily accessible to those who choose to follow the trail, and I hope many will