Robert Waddington and Heather Hughes

Two posts to report on our research on Mahomet Thomas Phillips so far, to coincide with the exhibition we have prepared for Black History Month 2022. The exhibition can be viewed in the University of Lincoln Library (October-December 2022) and, during October, at St Chad’s Church, Dunholme (where one can also view one of Phillips’s earliest church sculptures).

How the quest began

In February 2021, Revd. Adam Watson, vicar of Dunholme, Scothern and Welton, invited the Reimagining Lincolnshire project to St. Chad’s church in Dunholme to examine how artefacts and church furnishings might yield neglected stories of diversity. A guide to the church, thought to have been written some decades ago by the local historian Terence Leach, mentioned the following: “The carved wooden Chancel Screen was a gift from Captain Leyland Stephenson in memory of his wife, a relative of the Wild family. It was erected in 1913. It was built by Bowman’s of Stamford, the rood figures were carved by one Mohomet (sic) Phillips, a Congolese sculptor.” [i]

Pevsner’s The Buildings of England: Lincolnshire (1989 edition) included one reference to this sculptor and that was also in relation to Dunholme St Chad’s: ‘SCREEN. 1913, made by Bowmans of Stamford, with carved figures by Mahomet Phillips.’ [ii] At this stage, it appeared that this example may have been a curious one-off. Nevertheless, we were intrigued: why were there carvings by a Congolese man in this Lincolnshire church? Could we find out more about this gem of local knowledge, left to us in the church guide?

Initial searches online brought up precious little about Mahomet Phillips. One wiki entry was all we could find. [iii] Wikipedia does not permit original research or research based on primary sources; any entry must reference published sources. While this is an understandable requirement, it is a major stumbling block to redressing imbalances in this ‘people’s encyclopaedia’. As this wiki article lacked references to published sources, it was parked on a subsidiary site. It was dated 2020, so we hoped it was by a living descendant of Mahomet Phillips, possibly based on information or documents in the family’s possession.

That one wiki entry did give us sufficient leads to continue our research and led us to visit the Royal Geographical Society in London, where the papers of Richard Cobden Phillips, Mahomet’s father, have been deposited; the deposits of documents from Bowman & Sons of Stamford, for whom Mahomet worked, held at the Lincolnshire Archives; and the Royal Institute of British Architects archive at the Victoria and Albert Museum. Further, we were delighted to discover that the wiki article was indeed written by descendants of Mahomet Phillips, who generously gave us access to their wonderful family collection of day books, sketch books, photographs and cuttings.

We were soon to learn that the Dunholme rood was very far from being a one-off curio. His work is hidden in plain sight, everywhere: sculptures for churches, cathedrals and war memorials, up and down the country. It was made in a Gothic revival style that blends seamlessly into its surroundings in our churches, churchyards and public squares. The Gothic revival, which had become popular by the mid-nineteenth century and remained so into the early twentieth, resembled the work of medieval masons. So, these new works had the appearance of being more ancient than they actually were. Thus these quintessentially English sculptures, carved in wood, stone and marble and placed at the traditional and historical hearts of local communities, were the work of a black man from the Congo.

Mahomet Thomas Phillips: background and early life

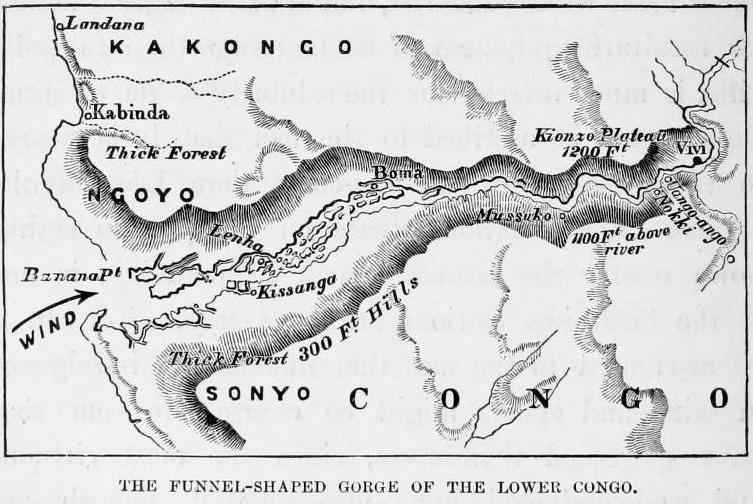

Mahomet Thomas Phillips was born on 1 June 1876 in the settlement of Banana at the mouth of the Congo River. [iv] He was one of four children born to English trader Richard Cobden Phillips, and a black woman from Cabinda, Nené Bassa, also known as Menina Barros.[v] (In one letter, Richard explained their relationship: ‘She is Mamai, meaning Mrs’. [vi]) Richard was the son of the vicar of Hindley, near Wigan. [vii] The Phillips family was learned and talented but far from wealthy. Richard’s nephew, Ernest Harrison, recalled of him that although he found modest fame, he was ‘bereft of any business sense so that he remained materially poor until the end of his life’.[viii]

Richard arrived on the Congo in the early 1870s and stayed for around 16 years. He worked as a factor for Hatton & Cookson of Liverpool, a company that specialised in the palm oil trade in Gabon and the Congo. [ix]

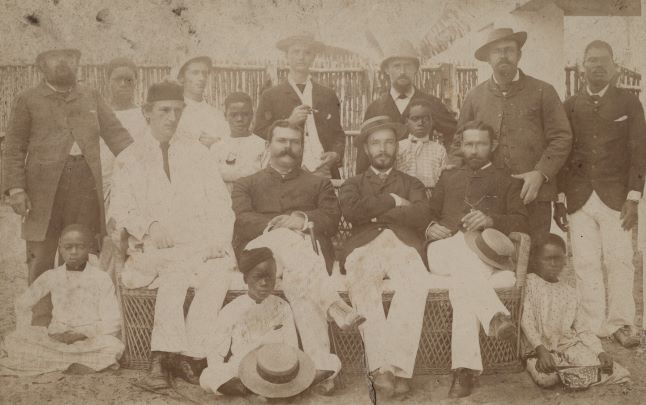

The company had factories, or trading stations, at Cabinda, Banana and up the river at Punta de Lenha. During his time at Banana, he became acquainted with the Welsh-American journalist and explorer, Henry Morton Stanley. [x] It is believed that he entertained Stanley during his expedition of 1869-1871, in search of the missionary and explorer, David Livingstone. [xi] Stanley began his second expedition in 1874 from the lower Congo. He returned in 1879 with the financial backing of King Leopold III of Belgium, to exploit the region’s considerable natural wealth; this was accompanied by the brutal treatment of local people. There are two photographs of Stanley in the National Portrait Gallery that were taken by Richard Cobden Phillips, probably dating from their 1874 encounter. [xii]

Letters between Richard and Joao Barros Franque in the Royal Geographical Society collection suggest that Nené likely belonged to one of the wealthiest and most powerful families at Cabinda, the Franques. [xiii] A man named Kokelo was the founder of the family fortune in the late 1700s. He had been the servant of a French slave trader who died at Cabinda, leaving his possessions to Kokelo, who named himself Franque Kokelo in honour of his benefactor. Kokelo used his connections to engage in the slave trade on his own account. He sent his son, Francisco (born c.1777), to Brazil to be educated. He was baptised as a Catholic, learned to read and write Portuguese and adopted Portuguese clothing. He was away 15 years, returning around 1800 in his early 20s. He became a ‘merchant prince’ at Cabinda. He imported Brazilian tutors for his sons, of whom one was called Joao. Francisco used his education and Brazilian connections to grow ever more powerful in the slave trade and became the principal African supplier of enslaved people to Manuel Pinto de Fonseca, the leading Rio de Janeiro trader. He made several later visits to Brazil and was member of a delegation to the exiled Portuguese court in 1812, to promote trade with Cabinda. It seems that Nené was one of Joao’s daughters.

Mahomet and his brother Paul were sent to a mission school at Mukinvika, on the south side of the River Congo. Two of the missionaries there were I.J. White and Arthur Billington. [xiv] In a letter to his mother thanking her for books and toys she had sent them, Richard noted that they were making good progress at school. Nené had visited them there and ‘brought away a good opinion.’[xv]

This was certainly a momentous time to grow up on the Congo River. From the late 1870s, the Phillips family witnessed the intensifying colonial conflicts in the region between the British, Portuguese, Dutch, Belgians, French and Germans, in what became known as the ‘Scramble for Africa’. There were gunboat battles along the river as rivals vied for control of territory and resources; the culmination was the Treaty of Berlin of 1884, according to which European imperial powers carved up most of Africa between themselves. The lower Congo region was divided between Belgium and Portugal and the British were forced out. Hatton and Cookson and other British traders relocated their interests further north, along the West African coast.

Coinciding with these events, the relationship between Richard Cobden Phillips and Nené Bassa broke down. [xvi] Two of their children, Mahomet and Nené, were sent to England, while Sara and Paul remained with their mother. According to family tradition, Paul was tragically taken by a crocodile. Richard himself was back in England by 1888. In that year, he presented a paper at the Royal Anthropological Institution; [xvii] he aspired to be recognised as an authority on the indigenous people of West Central Africa. He had some other contributions published in British newspapers and corresponded with several German and British geographical and anthropological societies.

Part II picks up the story of Mahomet Thomas Phillips’s life in the UK.

[i] Welcome to St Chad’s Dunholme: A History of the Church Building. n.d, n.p., p.5

[ii] Pevsner, N., Harris, J. and Antram, N. The Buildings of England: Lincolnshire. Penguin, 1989, p.260.

[iii] Mahomet Thomas Phillips at https://en.everybodywiki.com/Mahomet_Thomas_Phillips (accessed 17 October 2022)

[iv] Mahomet Thomas Phillips at https://en.everybodywiki.com/Mahomet_Thomas_Phillips (accessed 17 October 2022)

[v] From the timeline in the Phillips family archive, with grateful thanks.

[vi] Richard Cobden Phillips letter to I.J. White, 9 July 1884, Letter Book (p.232), GB 0402 Richard Cobden Papers, Royal Geographical Society.

[vii] Obituary of Mahomet Thomas Phillips in Lincoln, Rutland & Stamford Mercury, 11 June 1943.

[viii] Harrison, E.J., A resume of my chequered career. In Journal of Combative Sport 1999, at Journal of Combative Sport: My Chequered Career (ejmas.com)

[ix] Dennett, R. E. Seven Years among the Fjort: Being an English Trader’s Experiences in the Congo District. Hansebooks, 2020. Originally published in 1887 and available at the Internet Archive at https://archive.org/details/sevenyearsamongf00denn/page/n7/mode/2up. See also Anstey, R. E., British trade and policy in West Central Africa between 1816 and the early 1880s. In Transactions of the Historical Society of Ghana 3, 1, 1957, 47-71.

[x] See https://www.joh.cam.ac.uk/library/library_exhibitions/schoolresources/exploration/stanley/ 15 Oct 2022

[xi] Obituary of Mahomet Thomas Phillips in Lincoln, Rutland & Stamford Mercury, 11 June 1943; Bowman Deposit, Lincolnshire County Archives.

[xii] See National Portrait Gallery, 1877 entry on Stanley, at https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/personExtended/mp04254/sir-henry-morton-stanley?tab=iconography (accessed 15 October 2022).

[xiii] Information on the Franque family is from Martin, P. Family strategies in nineteenth-century Cabinda. In Journal of African History 28, 1, 1987, 65-86.

[xiv] Other than the letters in the Richard Cobden Papers, we have not yet found much information about this mission school. See entry on Billington in Biographie Belge d’Outre-Mer T.VI. 1968 col.4, at https://www.kaowarsom.be/documents/bbom/Tome_VI/Billington.Arthur.pdf (accessed 17 October 2022).

[xv] Richard Cobden Phillips letter to I.J. White, 9 July 1884, Letter Book (p.233), GB 0402 Richard Cobden Papers, Royal Geographical Society.

[xvi] Letters in Phillips family papers.

[xvii] Richard Cobden Phillips, The Lower Congo, a sociological study. Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, 17, 1888 pp.213-237. See also Heather Hughes, https://www.fromlocaltoglobal.co.uk/scientific-racism (accessed 17 October 2022)