Andrew Walker

Finding Gypsy Voices

In any project to expand and diversify Lincolnshire history, significant attention needs to be paid to exploring the past of one of the longest-established minority groups in Britain: the Gypsy, Roma and Traveller peoples. These two blogposts for Gypsy, Roma and Traveller History Month 2022 indicate ways in which we can connect to their past in Lincolnshire, through readily available source materials.[1] The focus of the blogposts will be the Gypsy/Roma peoples; they are part of a broader category termed Travellers, which also includes itinerant groups such as showfolk and boaters, who also deserve more attention.[2] This research takes its inspiration from influential social historians who have sought to rescue social minorities from the ‘enormous condescension of posterity’, to use E.P. Thompson’s memorable phrase.[3]

Rev. George Hall (1863-1918), born in Lincoln and eventually rector of Ruckland, Louth, was known as the ’Gypsy’s Parson’. He spoke their language, had a deep knowledge of their history and advocated for their rights.[4] Like Hall, another regular Lincolnshire contributor to the early issues of the Journal of the Gypsy Lore Society in the early twentieth century was William Cragg of Threckingham House, near Folkingham.[5] Unfortunately, the words and voices of the Gypsies themselves are heavily mediated in such accounts as these and others such as court reports; their own voices are conspicuously absent from the record.

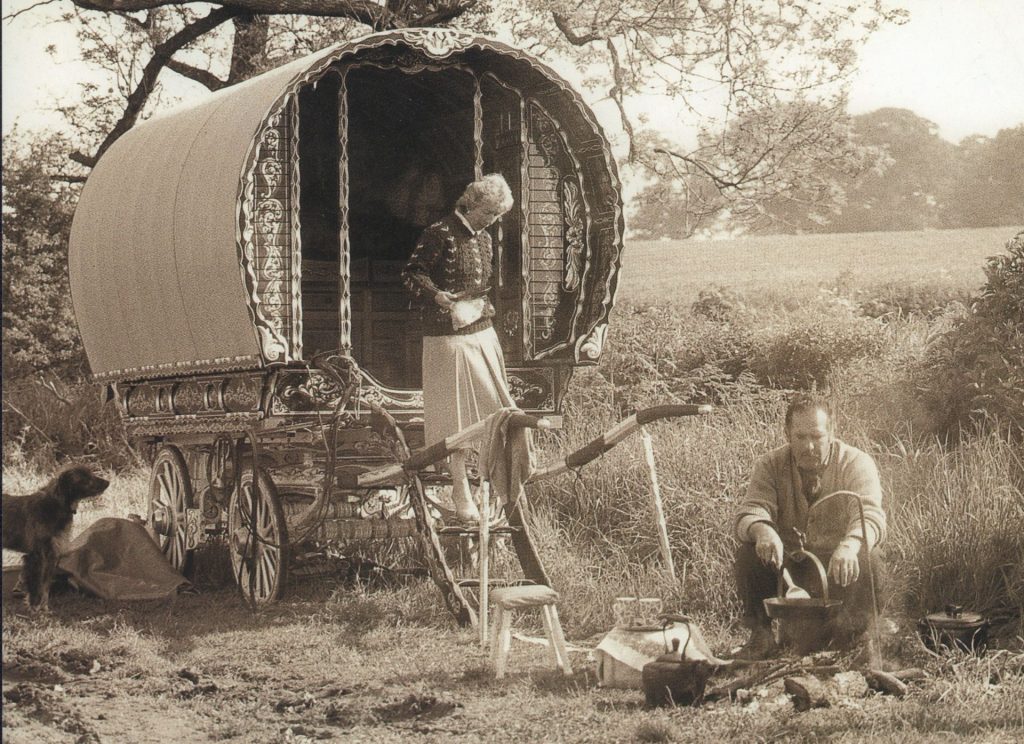

Gypsy heritage and culture have always been predominantly oral; it is estimated that in Victorian England, the literacy rates of Gypsies were between 3 and 12 per cent.[6] A notable exception is Gordon Silvester Boswell’s The Book of Boswell: Autobiography of a Gypsy.[7] Boswell (1895-1977) had strong links with Lincolnshire. His son Gordon (1940-2016) founded the Gordon Boswell Romany Museum at Spalding, which has one of the finest collections of Gypsy vardos, or caravans, in the country.[8]

The Gypsy Presence in the Census

A long-term Gypsy presence in Lincolnshire is suggested in place names. For example, census enumerators’ returns for the county record people living at Gipsy Bridge, Thornton le Fen; Gipsy Drove, Langriville, Boston; Gipsy Hall, Long Bennington; various Gipsy Lanes in Gedney, Quarrington, Swineshead and Wrangle; and at Gipsey Road, Algarkirk. It is highly likely that Gypsies would have been associated with these locations and have left their mark in this way.

Tracing individual Gypsies is more of a challenge. Until 1861, travelling people were not generally recorded in censuses.[9] This is partly because of their own agency: in 1854, for instance, the Grantham Journal referred to ‘the curious trait of gipsey feeling’ that they should pass into another parish to escape enumeration.[10] One group of 16 Gypsies who did provide details to a census enumerator in 1851 were probably persuaded to do so by their hosts, Rev. Henry and Jane Holdsworth. It seems that the Holdsworths had allowed them to pitch their tents in the grounds of Fishtoft Rectory.[11]

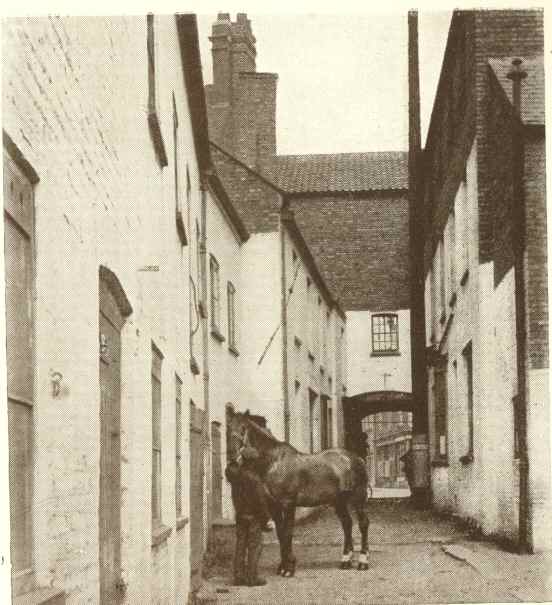

Just as some Gypsies were keen not to make contact with officialdom, some enumerators were also reluctant to engage with Gypsies themselves. It is not clear what prevented more detail being collected from an anonymous group of Gypsies at Northgate, Louth, in 1861, who were recorded as comprising two adult males and two adult females, all supposedly aged 40 years, together with two boys and two girls, all, (coincidentally again) aged ten years. In the census, Gypsies could sometimes be recorded in caravans, tents, at the side of the road, or on the highway heading to a particular settlement. In 1861, for example, 20-year-old Gypsy Joshua Boswell was recorded living in a stable between Main Street and South Street, Owston, near Gainsborough. Most Gypsies in Lincolnshire, as elsewhere, tended to be enumerated in family groups, usually nuclear in character, though occasionally with brothers or sisters of the household head in residence. It seemed rare to have Gypsy households containing more than two generations.

As the Table below indicates, Gypsies pitched their caravans and tents in a wide variety of different locations within the county. Given that every decade the census tended to take place in Springtime, it might have been expected to find a number of recurring locations.[12] This did not seem to be the case, however, apart from a couple of inns’ yards, the Duke of York in Boston (1881 and 1911), and the Red Lion, Wainfleet All Saints (1901 and 1911). It is likely that some publicans saw the arrival of the Gypsies as an opportunity to increase their trade. Successful attempts by local sedentary residents to deter Gypsies from returning repeatedly to the same specific location may have been the cause of the diversity of sites listed.

Table 1: Location of some Gypsy caravans and tents in censuses, 1861-1911*[13]

| Census Year | Location |

| 1861 | Hensam, Aubourn; Back Street, Heckington; Northgate, Louth; Owston; Poke Row, Skillington. |

| 1871 | Grassby, Caistor; Queen’s Head Yard, Caistor; Barton St Peter, Glanford Brigg; Village Green, Ingham; Northern Terrace, Lincoln; Butt Road, Messingham; George Street, Market Rasen; Great Hale, Sleaford; Market Place, Wragby. |

| 1881 | Ashby; Duke of York Yard, Boston; Crown Inn Yard, Skidbrooke; Wilsford, Sleaford. |

| 1891 | Heighington Road, Branston; Bunkers Hill, Gainsborough; Dawson’s Court, Lincoln; Gainsborough Road, Saxilby; Ings Lane, Whitton. |

| 1901 | Aisthorpe; West Street, Boston; East Common, Brumby; Gainsborough Road, Glentham; Brackenborough Road, Louth; Hibaldstow; Normanby; Westholme Lane, South Kelsey; Spridlington; Red Lion Yard, Wainsfleet All Saints; Carr Lane, Wrawby. |

| 1911 | Duke of York Yard, Boston; Hope Street, Clee; Dembleby Pits, Folkingham; Gladstone Street, Gainsborough; Mill Lane, Market Rasen; Bourne Road, Morton; Northgate, Sleaford; Moulton, Spalding; Red Lion Yard, Wainsfleet All Saints. |

*Travellers as per the broader meaning indicated above are excluded from this listing.

The occupations of Lincolnshire’s Gypsies listed in census records were in many ways what one might expect: horse dealing, hawking, chimney sweeping and, especially amongst women, peg making prevailed. The dependence of Gypsy families upon seasonal agricultural labour is inevitably understated, given the timing of enumeration.[14] Some Gypsy women’s involvement in fortune telling was not evident in the census returns, but was regularly reported, alongside their convictions, in the local press.[15]

To some degree, the travelling habits of Lincolnshire Gypsy families can also be discerned from census returns, especially for larger families, where the birthplaces of offspring provide an indicator of places visited. Most suggest that these circuits were not too extensive, with most Gypsy families appearing not to venture generally beyond a 30 or 40-mile radius of a given spot. In 1861, for instance, Clark Gray, a 23-year-old ‘gipsey horsedealer’, living at Hensam, Aubourn ‘on the highways’ was a head of a household with occupants born in Coleby, Sleaford, Horncastle, Navenby and Harmston. In 1901, Charles Mathieson, a 42-year-old Gypsy hawker, lived in a tent at Brumby with occupants born in Winteringham, Boston, Hook (Yorkshire), Boston, Lincoln, Gainsborough and Blythe, Nottinghamshire. It has been estimated that, on average, Gypsies would stop in a place for up to three or four weeks, after which the available wood, grazing and local trade would be exhausted. This suggested a round of about 12 stopping points a year.[16]

Analysis of recurring Gypsy family names is also possible from examining the census. Amongst the most common surnames in Lincolnshire during the Victorian and Edwardian periods were Booth, Boswell, Brown, Elliott, Gray, Lee, Mathieson and Smith. It was observed in the Grantham Journal in 1882 that although now not ‘every Smith is a gipsy, it was doubtless more likely that every gipsy was a Smith.’[17] Whilst many Gypsies’ forenames were not much different to the trends of the time, there are a number that stand out in the Lincolnshire records. Female names included Angulenay, Coriliander, Keytumas, Miseta and Senfie. Amongst males, Phoenix was a forename used across several generations in both the Boswell and Gray families. Other notable male names included Eldred, Mazerian, Mordecai, Taiso, and Teoben.

It was important to Gypsies to baptise their children. One notable Lincolnshire baptism took place in 1855, which was reported in the Stamford Mercury. Some Gypsies had encamped at Hagworthingham and presented a new-born infant to the rector for baptism. The clergyman’s wife and daughter, with the parish clerk, became sponsors or godparents, and the older godmother presented the baby girl with two dresses.[18] Before 1834 during the period of the old Poor Law, proof of settlement through baptism could enable access to minimal support in times of distress.[19]

Andrew Walker is a historian of Lincolnshire. He worked at the University of Lincoln from 1992 to 2010, latterly as Head of the School of Humanities and Performing Arts. Between 2010 and 2020, Andrew was Vice Principal of Rose Bruford College. He is an active volunteer researcher for Reimagining Lincolnshire.

Notes

[1] The modern spelling of ‘Gypsy’ is used throughout the text, although variants are retained in quotations. Other variants such as ‘gipsy’, ‘gipsey’ and ‘gypsey’ are often found within primary sources.

[2] Naming terminology is explored in the Travellers’ Times short video, https://www.travellerstimes.org.uk/heritage/roads-past-short-history-Britains-Gypsies-Roma-and-Travellers# [accessed 18 June 2022]. Roma people who originated in northern India were often called ‘Egyptians’ when they arrived in western Europe; in time this was shortened to ‘Gypsy’. Because the term ‘Gypsy’ is most common in the historical reports that these blogposts cover, that is the term used here – although more generally, our project respects and follows the Travellers’ Times usage.

[3] Historical works on Gypsies and Travellers include the following: David Cressy, Gypsies. An English History (Oxford, 2018); Jeremy Harte, ‘On the far side of the hedge’: Gypsies in local history’, The Local Historian 46, 1, January 2016, 27-46; David Mayle, Gypsy-Travellers in Nineteenth Century Society (Cambridge, 1988); Becky Taylor and John Hinks, ‘What field? Where? Bringing Gypsy, Roma and Traveller history into view’, Cultural and Social History, 18, 5, December 2021, 629-50; E.P. Thompson’s phrase can be found in his book, The Making of the English Working Class (London, 1963), 12.

[4] George Hall, The Gypsy’s Parson: His Experiences and Adventures (London, 1915). There is free access to this work at www.gutenberg.org/files/46015/46015-h/46015-h.htm [accessed 18 June 2022]. Reimagining Lincolnshire researchers visited St Olave’s, Ruckland, in the summer of 2021; George Hall was well remembered there in an exhibition devoted to his life and work.

[5] See correspondence from William Cragg in the Journal of the Gypsy Lore Society in 1908 and 1909. William Cragg (1860-1950) was a Lincolnshire farmer and landowner, who had a longstanding interest in the county’s past. He was Treasurer of the Lincolnshire Archaeological Society for 30 years.

[6] Harte, ‘On the far side of the hedge’, 31.

[7] Silvester Gordon Boswell, The Book of Boswell: Autobiography of a Gypsy. Edited by John Seymour (London, 2012). This work was originally published in 1970.

[8] For details of the museum, see www.romaniarts.co.uk/the-boswell-romany-museum/ [accessed 14 June 2022].

[9] Harte, ‘On the far side of the hedge’, 36. Details of baptisms, marriages and burials relating to Lincolnshire Gypsies can be accessed via ‘The Lincolnshire Travellers Birth, Marriage and Death Certificates and Parish Register Collection’ section on the Romany and Traveller Family History Society website. See www.rtfhs.org.uk [accessed 15 June 2022].

[10] Grantham Journal, 1 May 1854.

[11] The 16 Gypsies, mainly born in Norfolk, appeared to comprise three household groups. See 1851 census return for Fishtoft Rectory (www.findmypast.com).

[12] The census dates were as follows: 7 April 1861, 2 April 1871, 3 April 1881, 5 April 1891, 31 March 1901, and 2 April 1911.

[13] All census data extracted from www.findmypast.com.

[14] The 1939 Register, conducted on 29 September, just after the start of the Second World War, provides some information about Gypsies’ seasonal farm work. At Luddington on the Isle of Axholme, for instance, 57 occupants are recorded in Gypsy caravans. Most of the adults listed were engaged in casual agricultural work.

[15] For instance, Mary Ann Sherriff was gaoled for deception following a fortune-telling episode in Skellingthorpe; and ‘a gipsey fortune teller’ known as the ‘Gipsy Queen’ was gaoled for a similar offence in Skegness. See respectively Lincolnshire Chronicle, 25 March 1864 and Spalding Guardian, 8 October 1881.

[16] Harte, ‘On the far side of the hedge’, 37.

[17] See Grantham Journal, 23 December 1882. The report noted that the most prevalent Lincolnshire Gypsy surnames besides Smith were Elliott and Gray.

[18] Stamford Mercury, 12 January 1855.

[19] Harte, ‘On the far side of the hedge’, 32.