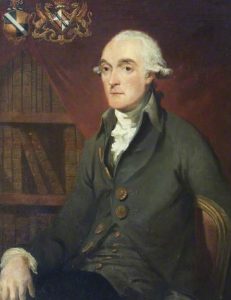

Francis Barber, born c. 1742, is best known as one of the servants in Samuel Johnson’s London household. He has appeared in the many biographies of Johnson and has himself been the subject of at least two. Aleyn Lyell Reade’s was published in 1912.[1] It claimed to be an exhaustive collection of all references to Barber in letters, memoirs, and biographies of Johnson; its emphasis was on Johnson’s beneficence rather than Barber’s personhood. The most recent is by Michael Bundock.[2] On the whole, people are more important than places in Bundock’s account, but that makes it easy to miss Barber’s connections to Lincolnshire.

Barber was born into slavery in Jamaica, probably on the sugar-producing Orange River estate on the northern shores of Jamaica, in the parish of St Mary. It was owned at the time by Colonel Richard Bathurst, a prominent member of the plantocracy. Barber’s earliest-known name was Quashey, one that frequently appears in slave name studies.[3] It is testimony to the tenacity of enslaved communities’ cultural memories, for it references a day of birth, Sunday, originating in the Akan speech area of West Africa.[4]

By 1750, Bathurst was in severe financial difficulties. He put his Jamaican estates up for sale and returned to Britain; for reasons that remain obscure, he brought Quashey, now seven or eight years old, with him. They stayed briefly with Bathurst’s physician son, also called Richard, in London.[5]

Not long after arrival, Quashey was baptised and given the name Francis Barber, symbolically severing him from his African and slave background. The choice of the new Christian name is not clear and no record has (yet) been found of his baptism. As Bundock notes, “either the relevant entry [in a London parish register] has not survived or the baptism took place elsewhere”.[6] There is at least a possibility that the ‘elsewhere’ was Lincoln. Bathurst senior’s home was in The Close, Lincoln, he made his will in Lincoln in 1754 and his burial occurred in St Mary Magdalene, Castle Hill, in the following year. The executor of his estate, Peter Lely, also lived in The Close.

He may well have brought Barber with him to the city, for he seems already to have selected a small school in Yorkshire for him to attend. Bundock asks the question, “why should Barber have been sent some 250 miles to go to school?” (p. 37) but this assumes a starting point in London. The choice makes more sense if Lincoln is taken as his point of departure. In any event he was not at school long; by early 1752, he had joined Samuel Johnson’s household.

Evidence suggests he was not entirely happy there. Col Bathurst’s will had decreed that “I give to Francis Barber a negroe whom I brought from Jamaica aforesaid into England his freedom and twelve pounds in money”. [7] Barber used his inheritance to take up a position as apothecary’s apprentice, and then to join the navy. It was Johnson who got him discharged some years later and he rejoined the household as Johnson’s personal servant. Ingledew describes his responsibilities:

“He performed all the routine duties of a valet, overseeing Johnson’s clothing, buying his provisions, reminding him of appointments, answering the door to callers and announcing their arrival to his master, or protecting him from unwelcome visitors, nursing him in sickness even to the extent of bloodletting, reading to him when his sight was too bad to let him do so himself, waiting at table, making coffee, fetching parcels from the post office, and booking coach seats for Johnson’s annual summer pilgrimages to such places as Oxford, Lichfield, Ashbourne or Lincolnshire, on which he accompanied and looked after his master. A number of tasks which Johnson thought might have been demeaning for Francis he would not let him do, such as buckling his shoes, or buying food for his cat, Hodge.” [8]

One of the Lincolnshire visits occurred in 1764, to Johnson’s close friend Bennet Langton at Langton Hall, near Spilsby. From this occasion is derived an insight into Barber’s physical attractiveness: Johnson is reputed to have told a group of friends some years later that

“When I was in Lincolnshire so many years ago, he attended me thither; and when we returned home together, I found that a female haymaker had followed him to London for love.” [9]

Johnson left £2000, the bulk of his estate, to Barber. While this was a very generous settlement, the amount was not given to Barber outright; rather, it was tied up in trusts, which included an annuity of £70 to be paid out of a lump sum of £750 administered by Bennet Langton. In a sense, this arrangement bound Francis Barber forever to Lincolnshire, although it is not known if he ever visited again. He and his family moved to Lichfield, where he died in 1801.

[1] Aleyn Lyell Reade, Johnsonian Gleanings Part II: Francis Barber The Doctor’s Negro Servant. Arden Press, 1912.

[2] Michael Bundock, The Fortunes of Francis Barber. Yale University Press, 2021.

[3] Handler, J and Jacoby, J. Slave names and naming in Barbados, 1650-1830. William and Mary Quarterly 53, 4, 1996, pp. 685-728; Burnard, T. Slave-naming patterns: onomastics and the taxonomy of race in eighteenth-century Jamaica. Journal of Interdisciplinary History 31, 3, 2001, pp. 325-346.

[4] Vincent Carretta, Francis Barber. Browse In Freedman/Freedwoman, 1775–1800: The American Revolution and Early Republic | Oxford African American Studies Center (oxfordaasc.com) accessed 11 October 2021.

[5] Reade, Francis Barber, p. 4.

[6] Bundock, The Fortunes of Francis Barber, p. 36.

[7] The will is reproduced in full in Reade, p. 3.

[8] Ingledew, J. Samuel Johnson’s Jamaica connections. Caribbean Quarterly 30, 2 1984, p. 7.

[9] Cited in Philip Butcher, Francis Barber, Dr Samuel Johnson’s Negro Servant. Negro History Bulletin 11, 2, 1947, p. 38.