Heather Hughes

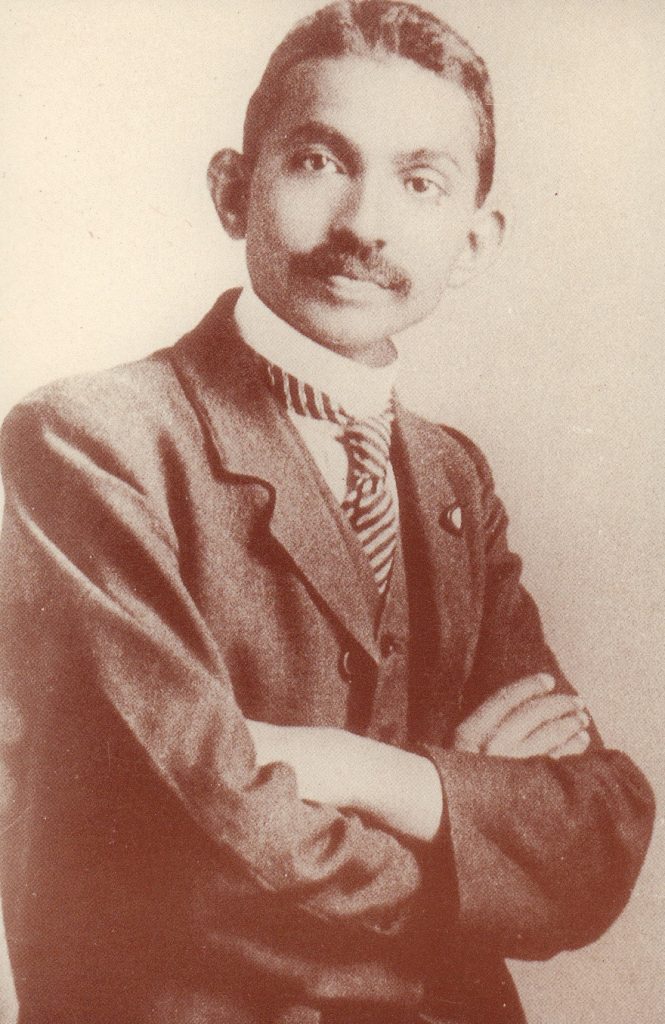

This is the story of how a vegetarian printer from Louth in Lincolnshire played a central role in Mahatma Gandhi’s early experiments with passive resistance against colonial oppression.

Albert Henry West was born in the market town of Louth in the Lincolnshire Wolds in 1879, the fourth child of Frederick and Betsy West. Frederick’s family had long farmed the Lincolnshire fens, around the small settlement of Wrangle. Frederick was born in 1837 and learned land surveying from his father (Albert’s grandfather) John, but did not stay on the land. Instead, he was apprenticed to his brother-in-law as a net and rope maker. A relative recalled of Frederick that ‘he was of medium stature and weight, very nimble and very neat in all his work and conduct.’ [i]

By the time of the 1881 census, Frederick was an independent rope maker in Louth and the family was living at 53 Aswell Lane in the town.[ii] Caitlin Green tells us that Aswell Lane formed the upper section of what is now Aswell Street; in the 1880s, there were inns and factories along the Lane, suggesting a working-class neighbourhood.[iii]

The Louth Museum holds a fragment of Albert West’s autobiography, written when he was in his ninetieth year.[iv] He recorded in it that school was never to his liking and he had left as soon as he could. He worked for his father for a while, and then accepted a position as printer’s apprentice in the town. He also attended art classes and must often have visited his country relatives; he later recalled in a different memoir that ‘I loved to be on the farms when I was a lad, although I did not become a farm worker myself.’[v] His father’s letters to him many years later were filled with reminders of old country traditions.[vi]

On completion of his apprenticeship, West spent eighteen months in Leicester, where he had been offered a job. Thereafter he moved to London, where he secured work as a printer for a shipping company. This enabled him to try life on board an ocean liner, which is how he came to arrive in South Africa.[vii] The South African War (1899-1902) had brought the whole of South Africa into the British empire, leading to a huge influx of white settlers, most of whom were British.[viii] By now in his mid-20s, Albert West decided to try life in Johannesburg and with a business partner, set up a printing press. Although he found this brash new mining town distasteful, there were evidently some compensations, such as Ziegler’s vegetarian restaurant. It was there that he met Mohandas K. Gandhi, according to his memoir:

“Around a large table sat a mixed company of men comprising a stockbroker from the United States who operated on the Exchange in gold and diamond shares, an accountant from Natal, a machinery agent, a young Jewish member of the Theosophical Society, a working tailor from Russia, Gandhi the lawyer, and me a printer. Everybody in Johannesburg talked about the share market, but these men were food reformers interested in vegetarian diet, Kuhne baths, earth poultices, fasting, etc.” [ix]

Gandhi was born in India in 1869 and trained as a lawyer in London. He had arrived in the Colony of Natal in 1893 to assist a wealthy Durban merchant, Dada Abdulla, in a legal case. Since 1860, Britain had transported some 40,000 Indians to the colony under conditions of indenture – one of many

such instances of moving unfree labour around the world to assist in the establishment of white settler economies.[x] In Natal, they were put to work on sugar, tea

and tobacco plantations, the railways and coal mines.[xi] On completion of their indenture, many had become successful small-scale fruit and vegetable producers, supplying Natal’s urban markets. Their relations with the African majority, as well as with white settlers, were fraught and complex. They had been brought to Natal precisely because white colonists had been unable to undermine Africans’ subsistence production, yet Indians’ agricultural success caused widespread resentment among many Africans.[xii] So-called ‘passenger Indians’, like Dada Abdulla, who had travelled to Natal on their own account, similarly faced enormous hostility.

Gandhi had not intended to stay long in Natal, but widespread anti-Indian sentiment, as well as his own experiences of racism, convinced him otherwise.[xiii] In 1894, he helped to found the Natal Indian Congress, specifically to look after ‘passenger’ interests, although it also addressed the broader issue of rights for all Indians as British subjects in Natal.[xiv] Two years later, he fetched his wife Kasturba and their sons from India; their lives were threatened by a white mob on the dockside as they disembarked.[xv]

Undeterred, Gandhi set up a legal practice in Durban and over the next few years, in addition to his political work, he began to elaborate his philosophy of satyagraha, involving passive or nonviolent resistance to injustice. As a pacifist, he helped to organise a stretcher corps during the South African War.[xvi] At the end of the conflict, with the Transvaal now under British imperial control, he moved to Johannesburg.

That is how Albert West and Gandhi came to meet. Several researchers have reminded us that vegetarianism was one practice within a wider progressive commitment to temperance, pacifism and often anti-colonialism.[xvii] Gandhi had long promoted vegetarianism and had had several articles published in The Vegetarian, published in London.[xviii] His and West’s common interests led to a firm friendship. They took frequent long walks together and joined mutual friends at out-of-town picnics, where spirituality and the meaning of life dominated conversation. As this description indicates, West had already been drawn to Gandhi’s politics:

“One evening I attended an Indian meeting addressed by him in the Indian Location, Johannesburg. Gandhi was the only speaker. The language was Hindi, which was understood by the large audience and listened to with rapt attention. The speaker stood erect and spoke quietly, without gesture or raising of the voice. As I looked upon that dark face in the dim light I felt that here was a leader of great power, but I could not foresee how great a national figure he was to become or how far and wide would be his influence throughout the world.”[xix]

An outbreak of pneumonic plague in Johannesburg in 1904 changed West’s life. Gandhi was closely involved in nursing the sick in the Indian Location, as was Viyavarik Madanjit, proprietor of Indian Opinion, the newspaper which Gandhi had recently founded in Durban. One of South Africa’s oldest anti-establishment newspapers, it has received the detailed attention it deserves in Isabel Hofmeyr’s fine study.[xx] Madanjit was just visiting Johannesburg but Gandhi considered his presence vital in dealing with the epidemic.

Gandhi therefore asked Albert West to take over the management of Indian Opinion. West readily agreed, made the necessary arrangements for his business in Johannesburg and set off for Durban – and a central role in shaping the profile of one of the best-known figures of the twentieth century. Gandhi came to rely on West as a close and trusted supporter. In turn, through Gandhi, West was drawn into an international British-Indian network of leading anticolonial politicians, writers and philosophers.

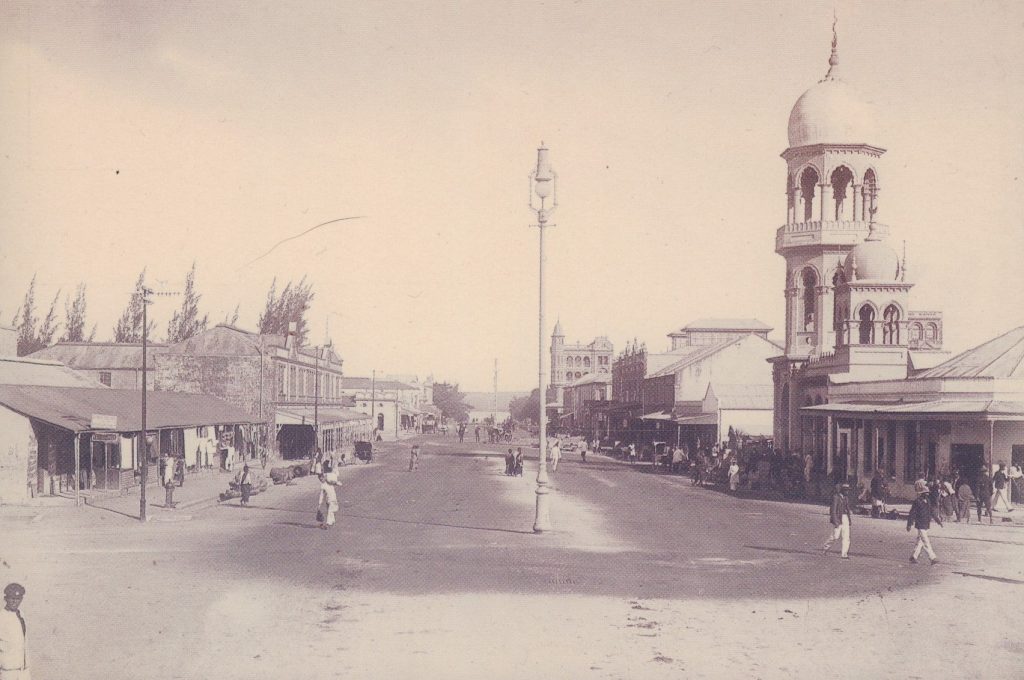

Indian Opinion was printed weekly in four languages (English, Hindi, Gujarati and Tamil) on a press in the Grey Street area of Durban, where most Indian businesses were located. West was to preside over a small staff of compositors, machinists and printers from India, Mauritius, St Helena and Natal – as a port city, Durban was widely connected to the Atlantic and Indian Ocean worlds. He soon discovered that profits were non-existent and agreed to work for a modest salary. As with all the other costs of the paper, this was provided by Gandhi, who was also overall editor.

Shortly after West’s arrival in Durban in 1904, Gandhi paid a visit to assess the paper’s financial situation. Another close friend, Henry Polak (later an editor of Indian Opinion and attorney in Gandhi’s practice), gave him a copy of John Ruskin’s Unto This Last to read on the train. It consolidated Gandhi’s thinking that worldly goods were a distraction and that asceticism, abstinence and self-reliance should take their place.

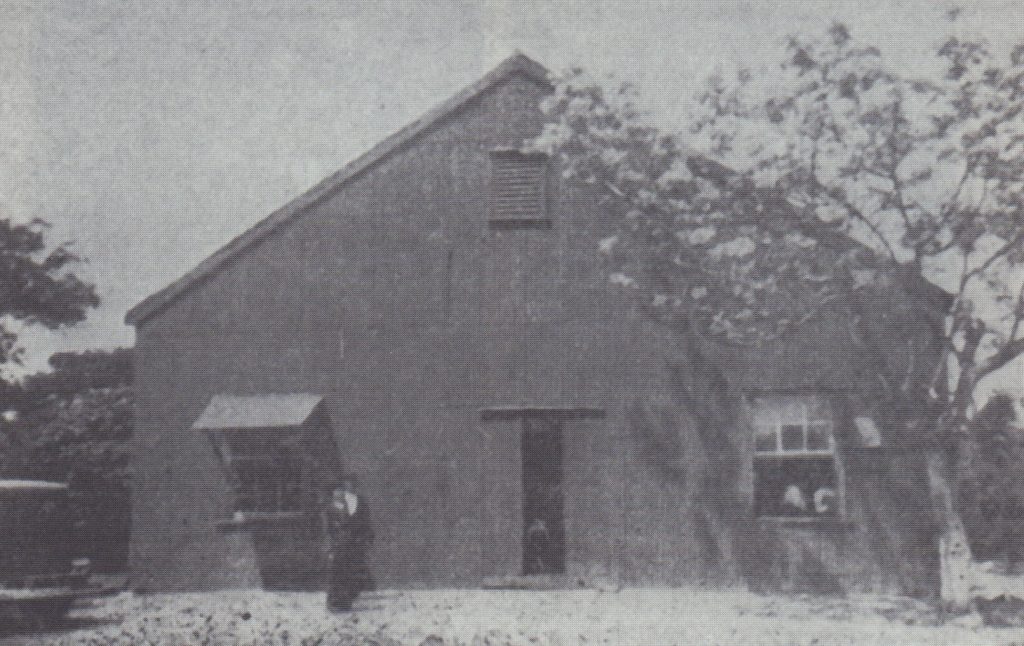

Preparations were begun at once for the founding of his first ashram. Gandhi purchased twenty acres of land on a former farm called Phoenix, some 14 miles inland from Durban. Though very rural, this was an area that was already, in Hofmeyr’s evocative description, ‘a brave new world of evangelical experiment comprising proselytising Trappists, mid-Western protestants, Zulu internationalists, Bombay Muslim holy men and Punjabi Arya Samajists.’[xxi]

Madanjit and several Indian Opinion co-workers thought the entire notion foolhardy and left; others among Gandhi’s associates wanted nothing to do with it. So West and the few remainers oversaw the founding of this historic site, including the relocation of press equipment:

“Type and machinery being very heavy and the road rough, with three rivers to cross, over which there were no bridges, we engaged four large farm wagons, with spans of sixteen bullocks each, and by this means we managed to remove the whole of the plant and stock in a day. It took a good deal longer than that to get it all sorted out and put in place.” [xxii]

It was a matter of some pride to them all that there was no interruption in publication. The first edition of Indian Opinion to be produced at Phoenix rolled off the press on Christmas Eve, 1904.

The ashram regime was demanding. Each of the Phoenix settlers had a simple cottage and a plot of land on which to grow food; each was also granted a monthly allowance of £3. Everyone was expected to participate in production, both on the paper and on the land, as well as in the daily tasks of reproduction: cooking, cleaning and maintenance. All this was achieved without electricity and only the most basic of tools. Not only was this to be a model of ascetic, communal living – ‘midway between a village and a joint family’, as one writer put it [xxiii] – but it was also preparation for satyagraha and likely periods in gaol. Simplicity, service, reflection, prayer: these became hallmarks of the communal outlook. Gandhi’s family moved to a wood and iron cottage at Phoenix, while he continued to oscillate between his legal work in Johannesburg and the new settlement. This caused him much anxiety but without the former, the latter would have been unthinkable.

Residents were soon drawn into community and political action beyond their farm. In 1905, for example, Natal was struck by devastating floods;[xxiv] according to West’s account,

“A relief fund was at once started and a large sum raised. A committee was appointed to administer the funds and this sat weekly in the office of the Protector of Indian Immigrants. I was asked to join this committee and in the absence of Gandhi, I was glad to be able to assist in granting compensation to the poor Indians who had suffered so heavily in the death toll and so badly by the destruction of their market gardens.”[xxv]

Here then, on the south-eastern African coastal strip, a bold experiment in self-help and resistance against imperial injustice developed. Albert West, one of Gandhi’s earliest disciples, was central to its foundation and growth. Yet it was also an enclave located in, and focused almost entirely on, a South Asian world in South Africa. Apart from a few individual sympathisers who crossed boundaries (and as we shall see, West’s family were among them), there was simply no basis, and too much ‘othering’, to make common cause with Africans at that time.

[Part 2 to follow]

*Thanks to Dr Victoria Araj for very helpful feedback and Prof. Uma Mesthrie-Dhupelia for support and permission to use family images.

[i] Information about the West family from https://www.matthew-west.org.uk/west-family-history/4-the-wests-of-wrangle and https://www.matthew-west.org.uk/west-family-history/1-elsoms-of-lincolnshire/2-the-wests-of-wrangle (accessed 8 April 2022)

[ii] 1881 Census entry for Frederick and Betsy West family, at https://www.findmypast.co.uk/transcript?id=GBC/1881/0014777516&expand=true (accessed 5 March 2022)

[iii] Caitlin Green, The Streets of Louth: An A-Z History. Louth, The Lindes Press, 2012, pp. 7-13.

[iv] Albert West, Autobiography of an Octogenarian. The Lifestory of One in his Ninetieth Year. Typescript fragment, PDF format. Thanks to Dr R Gatenby, Museum Archivist, for access to this source.

[v] Albert West, ‘In the early days with Gandhi’, at https://www.gandhiashramsevagram.org/gandhi-articles/in-the-early-days-with-gandhi.php (accessed 5 March 2022) This memoir was first published in The Illustrated Weekly of India in 1965.

[vi] See https://www.matthew-west.org.uk/west-family-history/4-the-wests-of-wrangle (accessed 8 April 2022)

[vii] Albert West, Autobiography of an Octogenarian.

[viii] This war, by far Britain’s most expensive and extensive imperial war of expansion, is more popularly known as the Anglo-Boer War, although this name excludes the countless black and brown people in the region who were caught up in it – from scouts and suppliers on both sides to those incarcerated in British concentration camps. See Peter Warwick, The South African War: Anglo-Boer War 1899-1902. London, Longman, 1980.

[ix] West, ‘In the early days with Gandhi’.

[x] Ashwin Desai and Goolam Vahed, Inside Indenture: A South African Story, 1860-1914. Durban. Madiba Publishers, 2007.

[xi] Uma Mesthrie-Dhupelia, From Cane Fields to Freedom: A Chronicle of Indian South African Life. Cape Town, Kwela Books, 2000.

[xii] Heather Hughes, ‘We will be elbowed out the country’: African responses to Indian indentured immigration to Natal, 1860-1910. Labour History Review 72, 2, 2007, pp. 155-168.

[xiii] The best-known example, which was to be transformative for Gandhi, was being thrown out of the first class carriage at the Pietermaritzburg train station in 1893. M.K. Gandhi, An Autobiography, pp. 93-4. In 1997, Nelson Mandela and Gopal Krishna Gandhi, Gandhi’s grandson and at the time India’s High Commissioner to South Africa, re-enacted the journey. Dhupelia-Mesthrie, From Cane Fields to Freedom.

[xiv] Surendra Bhana, Gandhi’s Legacy The Natal Indian Congress 1894-1994. Pietermaritzburg, University of Natal Press, 1997.

[xv] Gandhi, An Autobiography, pp. 160-163.

[xvi] Ashwin Desai and Goolam Vahed, The South African Gandhi: Stretcher-Bearer of Empire. Redwood City, Stanford University Press, 2013. This work explores Gandhi’s complex relationship not only with British authority but also with the African majority in South Africa.

[xvii] Elsa Richardson, Cranks, clerks and suffragettes: the vegetarian restaurant in British culture and fiction 1880-1914. Literature and Medicine 3, 1, 2021, pp. 133-153; Haejoo Kim, Vegetarian evolution in nineteenth century Britain. Journal of Victorian Culture 26, 4, 2021, pp. 519-533.

[xviii] For a link to his articles, see

https://ivu.org/index.php/history/2013-02-17-21-30-33/19-ivu/vegetarian-history/308-history-of-vegetarian-societies-in-africa (accessed 13 April 2022)

[xix] Albert West, ‘In the early days with Gandhi’.

[xx] Isabel Hofmeyr, Gandhi’s Printing Press: Experiments in Slow Reading. Cambridge, MA and London, Harvard University Press, 2013.

[xxi] Hofmeyr, Gandhi’s Printing Press, p. 59.

[xxii] West, ‘In the early days with Gandhi’.

[xxiii] James Hunt, cited in Hofmeyr, Gandhi’s Printing Press, p. 63.

[xxiv] Laljeeth Ramdhani, Natal: The Great Storm and the Floods of 1905. Durban, University of KwaZulu-Natal Gandhi Documentation Centre, 1984. Available at https://disa.ukzn.ac.za/sites/default/files/DC%20Metadata%20Files/Gandhi-Luthuli%20Documentation%20Centre/DOC%2001-01-84%20RAM/DOC%2001-01-84%20RAM.pdf

[xxv] West, ‘In the early days with Gandhi’.

This is an superbly researched and crafted piece. A fascinating and important part of Louth’s unwritten and unknown history

Brilliant , the scales fall from my eyes and the link to India publication excellent