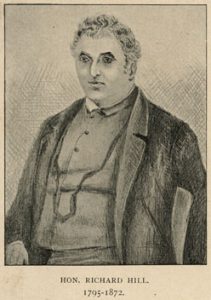

To mark International Abolition of Slavery Day on 2 December, this post features a prominent abolitionist with strong links to Lincolnshire, Richard Hill – someone who deserves to be far better known in this region.

Richard Hill was born in Jamaica on 1 May 1795. His father, also Richard, came from a well-established family in the Horncastle area and emigrated to Jamaica in 1779, with his brothers George Edward, Charles and Robert.[1]

Richard senior settled in Montego Bay, became a successful merchant and married a woman of colour. They had three children, Richard, Ann and Jane. In the pernicious race classifications of the time (how much ‘black’ blood was there?), Richard and Ann were registered as ‘quadroon’, while Jane was registered as ‘mestee’.[2]

When he was still very young, Richard junior was sent to live with relatives in England and attended the Elizabethan Grammar School in Horncastle. On his father’s death in 1818, he returned to Jamaica as the head of the household and to sort out inheritance matters. His father had already made him ‘pledge himself to devote his energies to the cause of freedom, and never to rest until those civil disabilities, under which the Negroes were labouring, had been entirely removed; and, further, until slavery itself had received its death-blow’.[3]

In pursuit of this end, Hill travelled widely in the Caribbean, the United States and Canada, and returned to England in 1827 to secure the assistance of the Anti-Slavery Society and its leading figures including Wilberforce, Buxton, Clarkson, Babington, Lushington and Zachary Macaulay. He delivered a petition to the House of Commons and remained in England for some time, writing and lecturing.[4]

It is of note that his sister Jane accompanied him to London; she remained in the UK until the early 1830s. Like her brother, she was active in the anti-slavery movement although frustratingly little is known of her role. According to Ryan Hanley’s Beyond Slavery and Abolition: Black British Writing c.1770- 1830, they seem to have been on good terms with Thomas Pringle, secretary of the Anti-Slavery Society, who was well connected to a network of black women in London. It is likely that the Anti-Slavery Society supported both siblings financially.

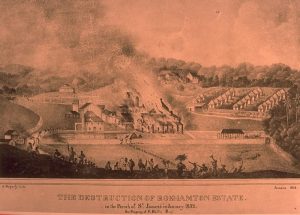

The Society sent Hill to San Domingo in 1830 to investigate social and political conditions there. His visit lasted nearly two years. Back in Jamaica, he was witness to the formal ending of slavery, for which he gave credit to the struggles of both enslaved and free black people:

‘The year 1830 saw the fires of rebellion lighted on the very mountains where the Maroon negroes had sounded the signal of insurrection thirty-five years before. The neighbouring valleys that had remained tranquil under the shock, were now the scene of general havoc and disorder. “Physical strength is with the governed.” That strength was felt, and roused into action … The struggle brought to a rapid close the question of colonial slavery. Two years after these events, in the month of July, 1834, I visited these very scenes in the quality of a magistrate specially commissioned to prepare both masters and slaves for the general emancipation’.[5]

Abolition was to be followed by a so-called apprenticeship phase, during which plantation workforces were to transition from slavery to wage labour. Hill was intimately involved in this process, having been appointed a magistrate to adjudicate cases between formerly enslaved apprentices and their employers. Although highly regarded by British officials, Hill found himself criticised for his perceived leniency towards apprentices; this led to him to resign his position.[6] He subsequently accepted the post of Secretary to the Special Magistrates Department at Spanish Town – a sort of ‘deanship’ of all the stipendiary magistrates [7] and a position he held until 1871.

James Thome and J. H. Kimball, the authors of an anti-slavery study of 1837, wrote of him,

‘We spent nearly a day with Richard Hill, Esq., the secretary of the special magistrates’ departments … He is a colored gentleman, and in every respect the noblest man, white or black, whom we met in the West Indies. He is highly intelligent and of fine moral feelings. His manners are free and unassuming, and his language in conversation fluent and well chosen…. He is at the head of the special magistrates (of whom there are sixty in this island) and all the correspondence between them and the governor is carried on through him. The station he holds is a very important one, and the business connected with it is of a character and extent that, were he not a man of superior abilities, he could not sustain. He is highly respected by the government in the island and at home, and possesses the esteem of his fellow citizens of all colors. He associates with persons of the highest rank, dining and attending parties at the government house with all the aristocracy of Jamaica.’[8]

He held many leading civic and political roles through his long career. These included Agent General of Immigration, and serving on the Privy Council, Board of Education and the Royal Society of Arts and Agriculture.

The last-mentioned is a hint of his greatest love: nature and the natural history of Jamaica, on which he published many scientific papers. He corresponded with Charles Darwin and the curators at the Smithsonian and advised the famous naturalist Philip Henry Gosse on his Jamaican research. His contribution to natural history is slowly being recognised – for example, Sessions’ recent study argues that Hill influenced Gosse to treat nature and emancipation as intimately linked.[9]

Hill also wrote extensively, and eloquently, on Jamaican history: A Week at Port Royal (1858), Lights and Shadows of Jamaica History (1859), Eight Chapters in the History of Jamaica, 1508-1680 (1868), and The Picaroons of One Hundred and Fifty Years Ago 1869). He died in 1872.

In very recent times, there have been attempts to remember Richard Hill in Lincolnshire. The Horncastle History and Heritage Society ran an event with students from the grammar school, which knew nothing of him until said event. The Society also discovered that Hill had corresponded with Horncastle historian, printer and auctioneer George Weir; letters between them are held in the National Library of Jamaica.[10]

There is a way to go before this crusading emancipationist and naturalist occupies a proper place in a reimagined Lincolnshire.

Heather Hughes

[1] F.J. DuQuesnay, Richard Hill – Son of Jamaica at http://www.jamaicanfamilysearch.com/Samples2/fred09.htm draws on family letters to shed light on his early life. [Accessed 1 December 2021].

[2] Elisabeth Griffith-Hughes, A Mighty Experiment: The Transition from Slavery to Freedom in Jamaica, 1834-1838. PhD Thesis, University of Georgia, 2003, p. 75.

[3] Frank Cundell, Richard Hill. The Journal of Negro History 5, 1, 1920, p.37

[4] Frank Cundell, Richard Hill, p.38.

[5] Richard Hill, Lights and Shadows of Jamaica History; Being Three Lectures Delivered in Aid of the Mission Schools of the Colony. Kingston, Ford and Gall, 1859, p. 93. Available at Lights and Shadows of Jamaica History: Being Three Lectures, Delivered in … – Richard Hill – Google Books [accessed 1 December 2021]

[6] Griffith-Hughes, A Mighty Experiment, p.75

[7] Monica Schuler, Coloured civil servants in post-emancipation Jamaica: two case studies. Caribbbean Quarterly 30, 3/4, 1984, p.95

[8] Jas A. Thome and J. Horace Kimball, Emancipation in the West Indies. A Six Months’ Tour in Antigua, Barbadoes and Jamaica in the Year 1837. New York, The American Anti-Slavery Society, 1838, p. 425-6.

[9] Emily Sessions, Anti-picturesque landscapes, entangled fauna, and interracial collaboration in post-emancipation Jamaica in the work of Philip Henry Gosse and Richard Hill. Terrae Incognitae, 53, 1, 2021, 26-47.

[10] Email Ian Marshman to Heather Hughes 22 July 2021. Many thanks to Ian Marshman, Chair of the Horncastle History and Heritage Society, for this information.