Heather Hughes

We mark International Women’s Day 2022 with an account of the representations of Matoaka, better known as Pocahontas, in St Helen’s Church in Willoughby, Lincolnshire. Her story is intimately bound up in United States foundational myths, which explains why there have been so many portrayals (and fabrications) of her in art, literature and film.[1]

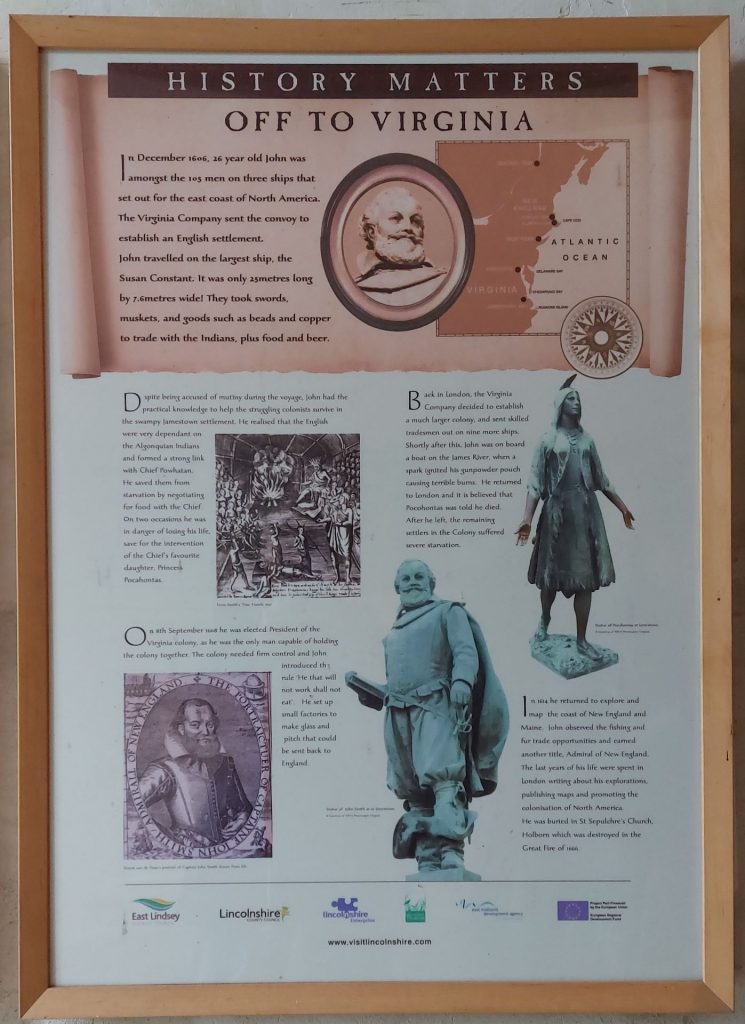

The connection to Willoughby is through John Smith, who was born there and baptised in St Helen’s in early January 1580. In his mid-teens, he went to sea and in that age of exploration, soldiering, piracy and adventure, fought as a mercenary in various dynastic struggles in Europe as well as against the Ottoman empire in the eastern Mediterranean. He became involved in the Virginia Company in London. Despite being accused of mutiny on the voyage (he was always a controversial character), he was a leading figure in founding the first permanent European settlement in North America, at Jamestown, in 1607.[2]

The settlement was not a happy one; apart from serious internal difficulties, relations with surrounding Native American polities were poor. By Smith’s own account, he was captured by members of the Powhatan polity and threatened with execution. Chief Powhatan’s young daughter, Matoaka, intervened to save his life. Thus arose the myth that the new country was founded on love and intercultural harmony.[3]

As many scholars have pointed out, ‘the story of Pocahontas and John Smith tells of an “original” encounter of which no even passably “immediate” account exists’.[4] Nevertheless, it has been endlessly embroidered to suit the needs of white Americans, in part by denying the violence and dispossession of colonial expansion. (By the same token, some Native Americans have regarded her as a traitor figure.)

Matoaka herself was captured in hostilities between the Powhatan and colonists in 1613 and converted to Christianity, taking the name Rebecca. She married colonist John Rolfe the following year; in 1615, she gave birth to a son and in 1616 the family travelled to London. She was feted in polite society as an example of ‘what a savage could become’; as they were preparing to return to Virginia, she became ill and died at Gravesend in Kent in 1617. She was only 20 or 21.

Her portrayal in St Helen’s thus arises from a claimed and very brief childhood association with John Smith, who had left Virginia in 1609, never to return. There are in fact three different portrayals, all from her young adult life. Two are in stained glass and another appears in an interpretive panel.

One stained glass scene depicts her receiving Christian instruction, presumably before her conversion, from Alexander Whitaker, ‘the Apostle of Virginia’. The image is, by any measure, deeply problematic, partly because it is a relatively recent addition in the church (1985). She is the only dark-skinned figure in the window, and she is semi-naked. Tattoos are visible on her arms. She is bare-breasted and seems to be demurely trying to hide her nakedness in the presence of the heavily-clad apostle, but only half succeeds. Her gaze is directed at the tall figure looking down on her, yet her facial expression is hard to interpret: is she interested, or is she ungrateful? Yet the gazes to which she, in her vulnerability, are subjected in turn are more powerful than her own, and they are all white (and in the artwork, male): that of the apostle, of the benefactor who paid for the glazing, Philip Barbour of Louisville, Kentucky; and those of the congregations and visitors, not all make of course, who have looked on the window since it was installed. It is hard to escape the demeaning othering.

This is in sharp contrast to her portrayal in another window on the south side of the nave. Here she is profusely clothed in fine garments, as she would have worn during her London visit. It is based on the only likeness made during her lifetime, an engraving by Simon van de Passe. This image was meant to show how very well integrated into settler society she had become. So integrated, in fact, that she is not obviously a person of colour; we know that from the elaborate surrounding scroll that bears the name ‘Pocahontas’. This time, her gaze is directed outwards to us, the viewers: she holds her own and relates as ‘one of us’. She looks far older than her 21 years.

The portrayal in the interpretive panel is an image of the famous statue that stands in historic Jamestown. Cast in bronze to mark the 300th anniversary of the founding of the Virginia colony (but only completed in 1922), we see a young woman with open arms, modestly clothed in a westernised imagining of Native American fringed garments, with neat shoes on her feet. The statue’s hands, we are told, have become shiny from all those who have held them to have their photos taken. A reproduction of this friendly, welcoming figure stands in the graveyard in Gravesend where she is buried.

Taken together, these images, as well as the context of their creation, underline the continuing complexities of Matoaka/Pocahontas, not only in US national myth but in the backstory of other key figures in the making of that myth. Their siting in a Lincolnshire parish church should also mean that they are acknowledged as difficult and contested heritage, which could open the way to meaningful dialogue about how we make our places of worship more inclusive.

[1] Monika Siebert, Pocahontas looks back and then looks elsewhere: the entangled gaze in contemporary indigenous art.. ab-Original: Journal of Indigenous Studies and First Nations and First Peoples’ Cultures 2, 2 (2018), pp. 207-226.

[2] For an overview, see Robert Appelbaum and John Wood Sweet (eds), Envisioning an English Empire: Jamestown and the Making of the North Atlantic World. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005.

[3] Derek Buescher and Kent Ono, Civilised colonialism: Pocahontas as neocolonial rhetoric. Women’s Studies in Communication 19, 2, 1996, 127-153.

[4] Peter Hulme, cited in Heike Paul, The Myths that Made America. Bielefeld, Transcript, 2014, p. 94.